Four Challenges to Aging in Place

Within 20 years, one in five Americans—almost 80 million people—will be older than 65 and, surveys indicate, they will want to remain in the current homes for as long as possible. However, the country currently lacks the accessible housing units and supportive social services needed to accommodate these desires.

Four challenges are particularly noteworthy, according to Projections and Implications for Housing a Growing Older Population, a recent Joint Center report which also projected that the share of households headed by someone over 65 will grow from 29.9 million today to 50 million in 2035. In particular:

- Most U.S. homes are not accessible for older people with limited mobility

- Many older Americans living at home will need long-term care, which is expensive

- Millions of older adults cannot afford their current housing units

- Older adults who live at home are often isolated

Challenge #1: Making Housing Accessible

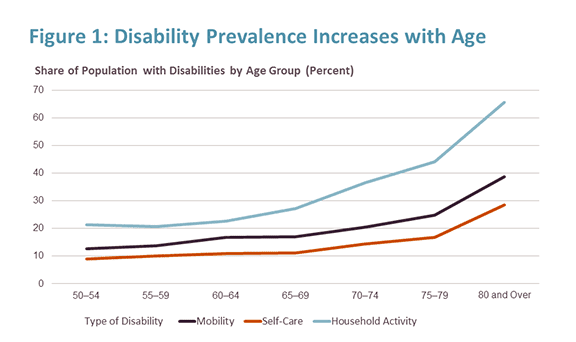

A growing older population will mean greater numbers of households that include someone with a disability (Figure 1). Indeed, the Joint Center projects that by 2035, 17 million older households will include at least one person with a mobility disability for whom stairs, traditional bathroom layouts, and narrow doors and corridors may pose challenges, a 77 percent increase from today. Yet only 3.5 percent of US housing units offer a zero-step entrance into the home, single-floor living, and wide doorways and hallways that accommodate someone in a wheelchair.

Source: JCHS tabulations of University of Michigan, 2014 Health and Retirement Survey.

The costs of improving safety and accessibility range from free (e.g. removing throw rugs) to costly (e.g. a new addition to enable single-floor living). Preparing ahead, at a time when the no one in the household has limited mobility disabilities, can help lower the financial and emotional cost of these changes—for example, during a bathroom remodel, adding reinforced walls can make the later addition of grab bars much simpler, while choosing a walk-in shower can eliminate the need to add one later. For some, merely identifying modification needs and finding a contractor or handyman to make changes can be daunting. Consequently, resources that can connect people to trustworthy sources to assess the home and find capable workers will be an important part of any efforts to support aging in place.

However, a sizeable share of homeowners will need financial assistance to make these changes. Today nearly 10 percent of all older homeowner households have less than $50,000 in total assets including the value of their homes. (Excluding the value of the home, 39 percent have less than $50,000.) Going forward, trends in income, wealth, and debt suggest that older adults may have even fewer assets in the future. Helping older adults with limited means finance modifications through tax credits, low- or no-interest loans, grants, or expanded Medicaid waivers for needed modifications will be important.

Renters, particularly those living in older, less accessible units, may be in more difficult straits. Even though federal law generally requires that landlords allow tenants with disabilities to make necessary changes to their units, renters—whose median wealth is only $6,000—typically must do so at their own expense. Furthermore, landlords may require the modifications be removed at renters’ expense upon leaving.

Challenge #2: Providing Long-Term Care

The Joint Center projects that the number of older adult households in which at least one person has a self-care disability will reach 12 million by 2035; many of these households will require daily assistance with personal care if they are to stay in their homes. (This is consistent with an often-cited 2005 study by Peter Kemper, Harriet L. Komisar and Lisa Alecxih estimating that nearly 70 percent of adults who reach the age of 65 will need some form of long-term care later in life.) Indeed, this type of care is increasingly being offered in people’s homes. Nursing home usage has declined in the past two decades, a trend likely to continue as health and housing partners build partnerships to deliver care at lower cost to private residences. In addition to assistance with personal care, by 2035, we project that 27 million older Americans will need help with other household tasks such as shopping, housework, or paying bills.

Yet long-term care currently is expensive. The median monthly cost for a home health aide working five days per week is $3,813. The typical older renter could afford just two months of these services before exhausting their savings. While the median older homeowner is better situated, many have limited resources—and as noted above may need these to make modifications to their homes.

Today most assistance is provided by family members, including spouses, at least in part because of high costs. However, in the future fewer family members will be available to the next generation of older adults, because the number of households with few or no children, as well as single-person households, will rise. For individuals, factoring in the potential costs of paying for in-home support and care is an important part of planning for aging in place, but policy has a role as well in encouraging innovation of cost-effective care delivery in the home.

Challenge #3: Ensuring that Housing is Affordable

Affordability is and is likely to remain a significant obstacle to aging in place. In 2014, 31 percent of older households were cost-burdened (i.e. they spent more than 30 of their income on housing). Holding cost-burdened shares by age, race/ethnicity, and tenure constant, the Joint Center projects that by 2035, 17.1 million older households will be housing cost-burdened, and 8.5 million of these households will be spending more than 50 percent of their income on housing.

Given lower incomes, older renters are more likely to be cost-burdened. However, with a homeownership rate approaching 80 percent for older households, owners are more numerous and make up the majority of cost-burdened older households. In particular, owners who carry mortgages into older ages—a trend that has increased over the past 20 years—are at higher risk of experiencing unaffordable housing costs. Households that are housing cost-burdened typically cope by cutting back on other necessities, such as food, healthcare, or transportation. These tradeoffs put older adults’ health at risk and limit their opportunities to engage in their communities and access needed services.

For homeowners, the challenge of high housing costs might be met with prudent and early financial planning, reverse mortgages or refinancing, relief from property taxes, or help increasing home energy efficiency and lowering utility costs. Renters have fewer options, as rental subsidies are in short supply. By 2035 the Joint Center projects that the number of older adults eligible for rental housing subsidies will grow to 7.6 million from just under 4 million today. Currently the nation provides subsidies to only about one-third of those eligible; simply maintaining this level for seniors in 2035 would require providing subsidies to an additional 1.3 million households, which would more than double the number of older people who are being assisted today.

Challenge #4: Reducing Isolation

Ensuring older households are able to connect with their neighbors and access services in their communities and beyond is as critical to aging in place as preparing one’s home and finances. One can be isolated anywhere, even in a city if streets are perceived as unsafe, or if friends or needed services are not nearby. There are, however, ways to capitalize on a localized population of older adults to deliver services, through organizations like “villages” or those that serve naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs), such as large apartment complexes that are home to significant numbers of older people.

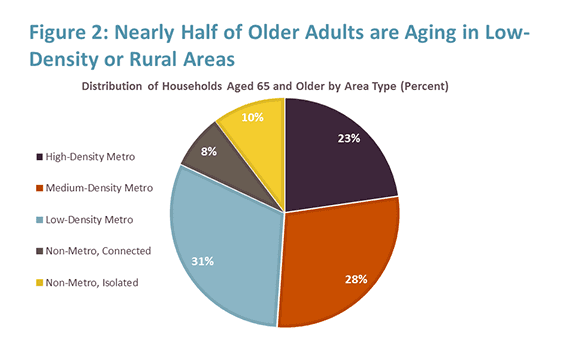

Isolation is a particular concern for those aging in low-density and rural locales. The new study found that that just under half of older households are located in areas of metro regions with less than one housing unit per acre, or outside metro regions entirely (Figure 2). When older adults curtail or give up driving—a share that exceeds 50 percent for those in their mid-80s and above—people living in these locations can be particularly isolated.

Source: JCHS tabulations of 2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates and USDA Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes.

Alternative transportation, such as paratransit or car-share services, as well as technology that enables virtual medical appointments and social interaction, will be key. But individuals in these lower density areas, and the organizations and governments that serve them, will need to consider how to expand programs to ensure older adults can access services and remain engaged in their communities.

Moving Forward

These challenges do not mean that aging in place is an impractical or an unworthy goal, but rather that there is much planning to be done at both the individual and societal level. Educating households about the financial and physical challenges they might face if they remain in their current home and the options available to address them is an important first step. So is ensuring that local governments understand and plan for the challenges their older residents will likely face.

For some, though, alternatives to a current residence may prove to offer a higher quality of life. Therefore, we also need to create new housing options that offer accessibility features, are located near to shopping and services (or in a multifamily building that provides services), offer flexible space (perhaps including space that can be occupied by caregivers if needed), and are aimed at a people with range of incomes, including low-income renters. Developing housing with these features in the centers or downtowns of small towns and suburbs where older adults already live can provide alternatives that allow longtime residents to maintain ties to their communities. Since one in three US households will be headed by an older adult within 20 years (up from one in five today), we need to start taking these and other steps as soon as possible.

—

Jennifer Molinsky will be a panelist at our March 6 event Housing and Policy in an Aging America. This event will be free and open to the public.