Older Adults Experience Disparate Outcomes When Relocating

As people age, changes in their physical and mental health may prompt them to move to a neighborhood or home that better meets their evolving needs. However, neighborhood inequality and residential segregation could limit the options that are available (or that older adults consider) when they move. In a new paper published in the Journal of Planning Education and Research, my co-authors and I explore whether older adults are able to move to neighborhoods with lower poverty rates. We found that there are substantial disparities in older adults’ destination neighborhoods, which can further perpetuate existing inequalities.

Older adults move at relatively low rates. About 6 percent of households headed by someone age 65 and older relocate, compared to 14 percent of younger households. But the sheer size of the older population meant that more than 3 million relocating households in 2023 were headed by an older adult, a number that is expected to increase as more baby boomers hit retirement age.

There are many reasons why older households might move. Some relocate to be closer to their children, to access a more age-friendly neighborhood, or to meet changing accessibility or affordability needs. But little is known about the actual characteristics or quality of the neighborhoods older adults relocate to.

In our paper, we use the restricted access version of the American Community Survey microdata from 2011 to 2019. For older adult households that moved, we can see what neighborhood they currently live in and what neighborhood they moved from. We use this to examine the characteristics of origin and destination neighborhoods. We focus in particular on change in neighborhood poverty rate. Poverty has documented links to resident health, but it is not a perfect proxy for neighborhood quality. To address this limitation, we use other socioeconomic indicators as well as neighborhood amenities to test the robustness of our findings.

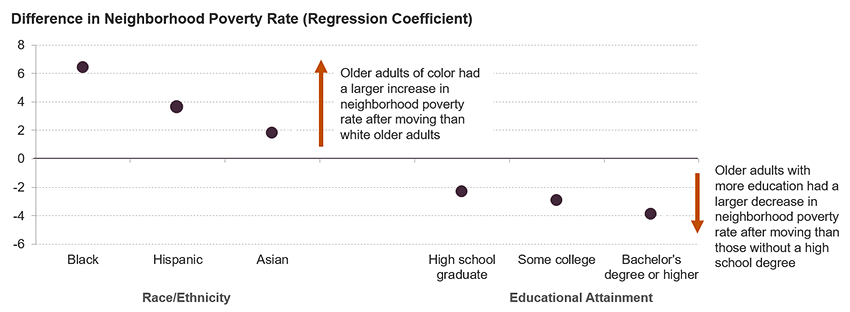

We find that older adults of color have a harder time making upward moves, reinforcing socioeconomic and neighborhood inequality. After moving, Black older adults saw an average increase in their neighborhood poverty rate that was 6 percentage points higher than what white older adults experienced (Figure 1). Similarly, older adults with lower educational attainment were disproportionately likely to relocate to higher-poverty neighborhoods than those with a college education. Having a college degree was associated with a decrease of about 4 percentage points in the neighborhood poverty rate as compared to older adult movers without a high school degree. These disparities were even more pronounced among renters and lower-income households.

Figure 1: Residential Mobility Outcomes Were Worse for Older Adults of Color and Those with Lower Educational Attainment

Source: Author tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2011–2019 American Community Survey Restricted Microdata.

These findings highlight the pressing need for housing and neighborhood planning that incorporates the diverse needs of older adults. Reducing housing costs through utility assistance and property tax abatements, providing housing search counseling, retrofitting homes for aging-related needs, and expanding in-home support services would all support our rapidly aging population. Such measures can help older adults stay in their communities or overcome the barriers for those who wish to relocate to neighborhoods that better support their health and well-being. At the same time, investments in local infrastructure and amenities in historically disadvantaged communities are crucial for older adults who choose to stay in their neighborhood because of the social ties they rely upon and value.