The Dual Burden of Housing and Care for Older Adults

As the first baby boomers turn 80 in the coming decade, a growing number of older households will face challenges paying for both housing and the supports and services they will need to remain in their homes. In a new paper out this week, we find that after paying for housing and basic living expenses, only 24 percent of single and partner households age 75 and over had sufficient income to afford a daily paid visit from a home health aide. Affordability rates were even lower for renters, households of color, and those with functional difficulties more likely to need care services. The paper builds on analysis reported in Housing America’s Older Adults 2023 and summarized in a 2024 blog post by including both single and partner households, expanding the metros included in the study, and focusing on in-home care.

A majority of older adults will need long-term care (LTC) services at some point in their lives, such as assistance with dressing, bathing, or managing complex medication regimens. Most older adults prefer to receive such care in their own homes. Yet the cost of paid LTC services is out of reach for many households. In 2021, one daily in-home visit by a health aide at the median national rate added up to $41,000 per year. Medical insurance, including Medicare, does not cover most LTC needs, and relatively few older adults have private long-term care insurance. LTC services at home are most likely to be paid for by Medicaid Home and Community Based Support (HCBS) waiver programs, which do not operate as entitlements, vary in coverage and availability by state, and are only available to those enrolled in Medicaid. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most LTC services are provided by unpaid caregivers, and the burden on family and friends can be high.

Our analysis of multiple data sources outlined in the paper found that only one quarter of the nearly 10 million households in our sample had enough income to pay for a daily care visit on top of housing and basic costs of living. Partner households were better positioned with 43 percent able to cover a daily visit (serving both partners) compared to 19 percent of those living alone. Tenure also mattered: less than 9 percent of renters were able to afford housing, basic expenses, and daily care compared to 30 percent of owners.

We found that Black and Hispanic households were least likely to afford care, with only 14 and 11 percent respectively able to fund LTC services out of income alone, compared to 26 percent of their white counterparts. And just 19 percent of households with a resident who struggled with mobility, self-care, and/or independent living were able to afford a daily care visit, though they were far more likely to need LTC services.

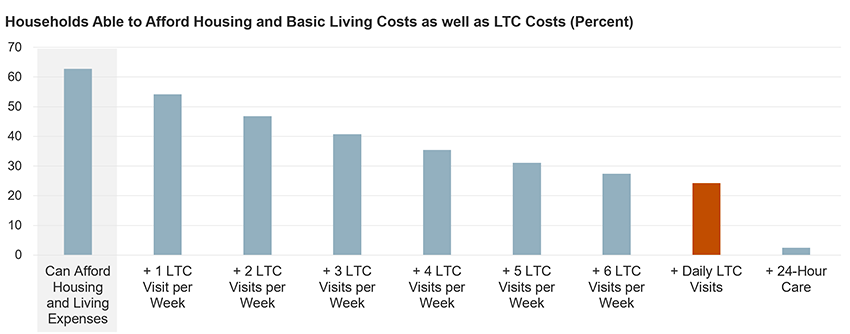

While a daily paid visit was out of reach for most, slightly more than half of households could afford one visit per week, and 30 percent could afford 5 weekly visits (Figure 1). Practically, periodic paid care could provide respite to unpaid family caregivers. However, even without considering the cost of a daily LTC visit, only 63 percent of the entire sample could afford their housing and basic costs of living (Figure 1, far left column). The remainder lacked sufficient income for any LTC care services.

Figure 1: Just 24 Percent of Older Households Can Afford to Pay Out-of-Pocket for Daily Care After Housing and Living Costs

Notes: Sample includes only single and partner households in metro areas with the younger resident at least 65 and the older resident at least 75. Households able to afford daily care have incomes higher than total housing plus living cost plus one daily four-hour visit.

Source: JCHS analysis of 2021 Genworth Cost of Care Survey data; US Census Bureau, 2021 American Community Survey; and University of Massachusetts, Boston 2021 Elder IndexTM.

Unsurprisingly, households earning under 50 percent of area median income (AMI) were unable to afford a daily care visit (Figure 2). Yet neither could 64 percent of those earning between 67 and 200 percent AMI—a range considered under a Pew Research Center definition to be “middle income.” This middle-income group is far less likely to be eligible for Medicaid-covered LTC services yet clearly lacks income sufficient to pay out of pocket.

Figure 2: Just One Third of Middle-Income Households Are Able to Afford Daily Care at Home Plus Housing and Living Costs

| SUFFICIENT income to pay for daily care plus housing and living costs | INSUFFICIENT income to pay for daily care plus housing and living costs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 50% AMI | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 50–67% AMI | 0.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 67–200% AMI | 36.3 | 63.7 | 100.0 |

| 200% AMI and Over | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

Notes: Calculations assume someone receiving care services at home is paying the median cost in their metro region for 28 hours per week of a home health aide and median area living costs. Median income is that of a person age 75 and over in the metro region. Sample includes only single and partner households in metro areas with the younger resident at least 65 and the older resident at least 75.

Source: JCHS analysis of 2021 Genworth Cost of Care Survey data; US Census Bureau, 2021 American Community Survey; and University of Massachusetts, Boston 2021 Elder IndexTM.

However, many middle-income households have housing wealth that might be tapped. We calculated the share of households in our sample that owned homes free-and-clear and could, in theory, borrow up to 80 percent of their home’s value. Those funds could allow 1.6 million households to fund LTC services for 5 years, increasing the share of our sample able to afford daily care from 24 to 41 percent at 2021 prices. We caution, however, that not all owners would likely secure financing to extract this much equity. Two-person households may also be more conservative about borrowing against their homes given potential future needs of the healthier partner. Additionally, given the disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic households unable to afford care, liquidating home equity limits potential intergenerational wealth transfers and may exacerbate the persistent gap in homeownership by race and ethnicity. Finally, renters, who by definition have no home equity, would see no improvement in LTC affordability.

There is no simple fix to the high costs of both housing and care, particularly as costs rise for both, and at a time when funding for federal programs is volatile. Fully funding Medicaid HCBS would help those with the greatest affordability needs, while coverage of LTC services by Medicare would help millions more. Addressing housing needs can also help older households make ends meet, including through expanded rental subsidies as well as home repair and modification assistance that ensure the home is a suitable and comfortable place in which to receive care.