Designing New Programs to Narrow Racial Homeownership Gaps

In the past two years a growing number of for-profit and non-profit lenders have created special purpose credit programs (SPCPs) that aim to address some of the longstanding policies and practices that have impeded homeownership by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) households. While these programs have similar goals, a review of initiatives that I carried out as a summer research assistant at the Center found that they often differ in significant ways.

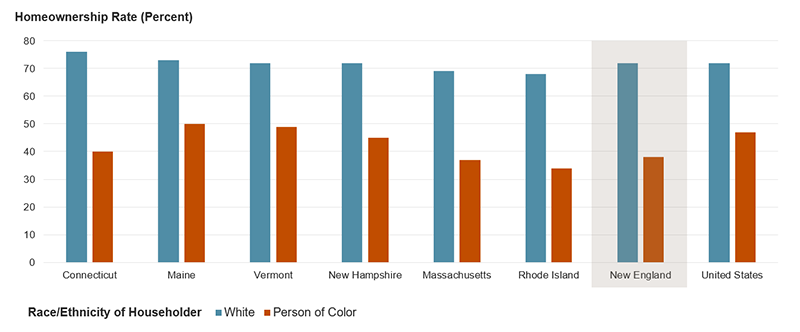

The programs attempt to address large racial and ethnic differences in homeownership rates. Across the US, 47 percent of households headed by people of color owned their home compared to 72 percent of white households, according to Center tabulations of the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey 5-Year estimates for 2015–2019. Racial homeownership gaps are even more pronounced in the six New England states, the geographic focus of my research, which was funded by the Federal Home Loan Bank of Boston. Just 38 percent of households headed by people of color owned their homes in the region compared with 72 percent of white households (Figure 1). Furthermore, these gaps are present in all six New England States and are widest for Black and Hispanic households.

Figure 1: People of Color Are Far Less Likely to Own Their Homes than White Households in New England and the US Overall

Several factors have contributed to these differences. Due to a history of exclusion and predatory financial practices along racial lines, households of color tend to have lower savings and are less likely to benefit from intergenerational transfers of wealth than white households. Discrimination has also resulted in households of color often having lower credit ratings than otherwise similar white households. And when potential homeowners of color do secure a mortgage, they often receive higher interest rates than white borrowers who have the same (or even less) income.

While the Fair Housing Act has prohibited explicit discrimination in housing since 1968, the passage of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) in 1974 expressly allowed for the creation of credit products that serve “an economically disadvantaged class of persons.” By permitting non-profit and for-profit lenders to extend credit on favorable terms to customers identified by a shared characteristic, ECOA created an opportunity for lenders to specifically address documented disparities in lending. However, until recently, few lenders have tried to use SPCPs to address racial inequities in homeownership.

To better understand the variety of approaches that organizations are taking with their SPCPs, I interviewed 18 practitioners responsible for 12 programs across the country, including five SPCPs. This research revealed several key decision points that entities have to make when creating an SPCP. These include the following:

Objectives

The SPCPs examined share similar ambitions, though their main objectives often differ. Initiatives like the Champlain Housing Trust’s Homeownership Equity Program emphasize expanding access to homeownership, especially for BIPOC households, while others, like the LISC San Diego Black Homebuyers Program, prioritize generating wealth in BIPOC communities, using homeownership as a tool toward that end. Another common objective is to create housing stability in BIPOC communities, which programs like the Chase Homebuyer Grant and Wells Fargo’s SPCP prioritize. While these objectives often overlap, each program’s priority informs its structure to a large extent.

Eligibility

One of the primary debates in designing an SPCP is whether it should be place- or people-based. Place-based programs use geography to designate potential customers. For example, the Chase Homebuyer Grant is offered to anyone buying a primary residence in one of 6,700 majority-Black census tracts. This approach emphasizes supporting existing BIPOC communities. However, critics note that such programs could subsidize homebuyers who are not economically disadvantaged, which could eventually displace lower-income households.

Historically, concerns about violating the Fair Housing Act made many lenders wary of people-based programs that use identifying characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, to determine eligibility. However, regulators, like the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), have indicated that SPCPs can use this approach, which has led to a growing number of people-based programs. For example, the LISC San Diego Black Homebuyers Program offers a downpayment assistance grant to Black first-time homebuyers in San Diego County who earn less than 120 percent of the area median income. In a similar vein, the Homeownership Council of America’s (HCA) National Down Payment Assistance Programs serve BIPOC first-time homebuyers earning up to 140 percent of AMI, as well as low-to-moderate income first-time homebuyers earning up to 80 percent of AMI, across the country.

Assistance

Many SPCPs provide downpayment assistance, either as a low-interest loan or as a grant. However, the amount of assistance varies considerably. At the lower end, the Chase Homebuyer Grant program offers a $5,000 grant that can be used as part of a downpayment or to reduce closing costs. At the upper end, the LISC San Diego Black Homebuyers Program offers a $40,000 grant. (Recipients can also receive an additional $9,000 grant from Union Bank, the program’s partner lending institution.)

Other approaches include offering lower interest rates or loosening underwriting guidelines. Wells Fargo’s SPCP is structured as a refinancing program in which all Black borrowers with an FHA mortgage in the Wells Fargo servicing portfolio qualify for a reduced interest rate (which was 3.75 percent in July 2022). TD Bank’s SPCP is a special mortgage product that uses broader debt-to-income and loan-to-value metrics for customers in qualifying majority Black/Hispanic census tracts, as well as a $5,000 lender credit that can be put toward a downpayment.

Terms

Entities offering SPCPs not only must decide whether downpayment assistance funds are being offered as a loan or a grant, but also whether the loan is forgivable. Some programs, for example, try to recycle funds and serve families in the future by providing low- or no-interest downpayment assistance loans that must be repaid when the home is sold. Alternatively, the Champlain Housing Trust Homeownership Equity Program offers first-generation BIPOC homebuyers up to $25,000 in downpayment assistance as a zero-interest loan that is fully forgiven after three years. This helps ensure that borrowers do not immediately flip their homes while also giving them the opportunity to accumulate wealth they can access when they sell their home or pass it on to an heir.

Other programs—such as the San Diego Black Homebuyers Program, the Chase Homebuyer Grant, and the credit component of TD Bank’s program—provide downpayment assistance as a grant that has few if any additional requirements related to them. The rationale is that homebuyers who benefit from family gifts for downpayments do not have to repay those funds, and do not have to abide by required periods of residency in the home, so program participants should be similarly unrestricted.

Entities developing SPCPs have to consider several other important factors, including how they reach potential recipients (who may distrust lenders), and whether programs should include more fine-grained eligibility requirements to ensure they reach the desired households. (For a good overview of these and other issues, see the SPCP Toolkit provided by the Mortgage Bankers Association and the National Fair Housing Alliance in partnership with HCA.)

As entities grapple with these questions, many have forged successful partnerships with community-based organizations to help conceptualize, implement, and evaluate these programs. Indeed, as more SPCPs are launched and more households use them, evaluating their effectiveness will be an important part of developing initiatives that can help narrow longstanding racial homeownership gaps.