How Has the Pandemic Affected Landlords?

As has been well documented, the financial consequences of the COVID-19 crisis have been severe, particularly for the nation’s renter households who have been more likely to report lost income due to the pandemic and, despite making dire tradeoffs and amassing significant debt, still have struggled to make rent. With roughly a quarter of renters spending over half their income on rent in a typical year, the pandemic has only exacerbated issues of housing affordability.

At the same time, comparatively less is known about how the nation’s private landlords—who supply the majority of the nation’s lowest-cost rentals—have fared during this crisis. In a new paper "How Are Landlords Faring During the COVID-19 Pandemic? Evidence from a National Cross-Site Survey," we surveyed residential rental property owners in ten US cities—Akron, OH; Albany, NY; Indianapolis; Los Angeles; Minneapolis; Philadelphia; Racine, WI; Rochester, NY; San Jose; and Trenton, NJ—to better understand the impact of the pandemic on landlords’ rental incomes and business practices. Nearly 3,000 individuals responded to our survey. Several key themes stood out.

First, given what is known about how many renters are behind on rent it is not a surprise that owners’ rent collection has decreased during the pandemic. The share of landlords who collected 90 percent or more of their potential rental revenue fell 27 percentage points from 2019 to 2020 (89 to 62 percent). In fact, each city in our sample saw a three- to fourfold increase in the proportion of landlords owed 10 percent or more of charged rent by year’s end.

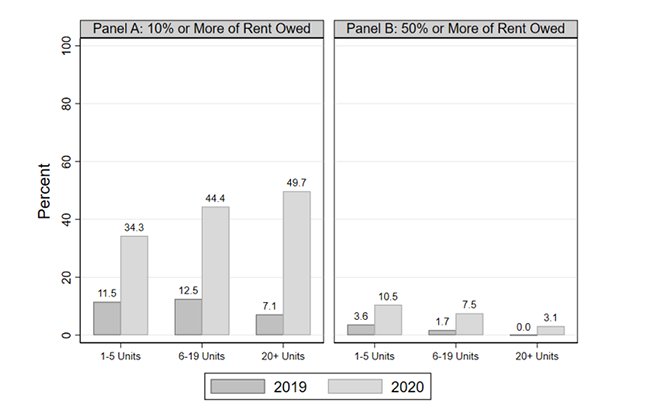

Figure 1 shows that, while shortfalls in rent collection affected all landlords regardless of the size of their portfolio, there were notable differences in these impacts. Owners with 20 or more units were more likely to have seen at least a 10 percent decline in revenues. However, smaller and mid-sized landlords, who had higher exposure to non-payment prior to the pandemic, were more likely to have seen rental revenues drop by more than 50 percent. Of particular note is that 10 percent of owners with five or fewer units—those most likely to provide affordable units—reported receiving at most half of their rental revenue during the pandemic.

Figure 1. Landlords’ Rental Collection Rate by Size of Landlord Portfolio

Notes: This figure plots the share of landlords reporting less than 90 percent of total rent received (Panel A) and less than 50 percent of total rent received (Panel B) in 2019 and 2020, by the size of landlords’ rental portfolios. Rental payment is expressed as a percentage of total rent charged, in a given year, for a landlord’s rental portfolio. 71.1 percent of landlords in the sample own 1-5 rental units, 18.2 percent own 6-19 rental units, and 10.7 percent own 20 or more rental units. Models include city fixed effects. The number of survey respondents in the sample is 2,524.

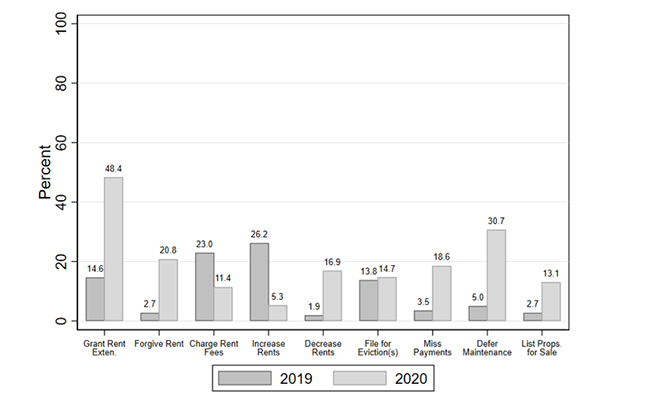

Second, owners of all sizes adjusted their management practices during the pandemic (Figure 2). For example, the share of landlords granting rental extensions and forgiving back rent in 2020 increased sharply relative to 2019 (15 to 48 percent and 3 to 21 percent, respectively). While these changes were driven in part by decreased rental revenue, our statistical models suggest that business impacts alone cannot explain landlords’ behavioral responses. Additionally, 31 percent of landlords reported deferring property maintenance in 2020 compared to only 5 percent in 2019. Finally, the share of owners who listed at least one property for sale increased more than fourfold from 2019 to 2020 (3 percent to 13 percent).

Figure 2. Landlords’ Rental Business Practices Prior to and During the Pandemic

Notes: This figure plots landlords’ rental business practices in 2019 and 2020. See text for a full description of each rental business practice. Responses do not sum to 1 because landlords could choose multiple actions. The number of survey respondents in the sample is 2,525.

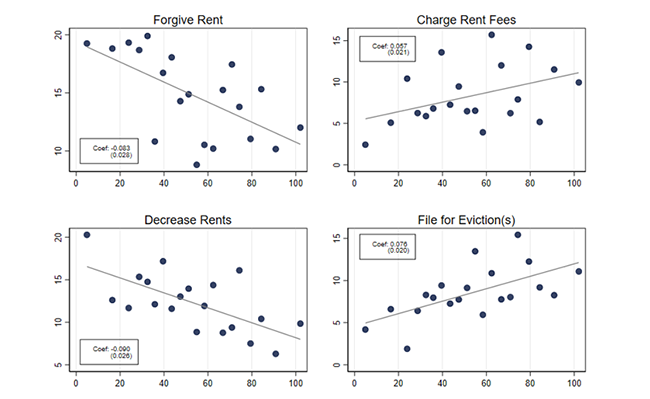

Finally, we find that renters of color have disproportionately borne the negative impact of landlords’ decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 3). While rental properties in communities of color were more likely to be moderately and severely behind on rent in 2020, landlords were also more likely to take punitive actions against tenants in these properties holding constant rates of rental collection. These punitive measures include applying late rental fees, filing eviction notices, and not offering rental forgiveness.

Figure 3. Landlords’ Property-Level Business Practices (y-axis) by Neighborhood Percent Residents of Color (x-axis)]

Notes: This figure presents binned scatter plots of landlords’ 2020 property-level rental business practices versus the neighborhood share of residents of color (for that property). A neighborhood’s share of residents of color is defined as the sum of individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, multiracial and/or other races. See text for full details on plot construction. The solid lines show the best linear fit estimated on the underlying micro data using OLS regression. The coefficients show the estimated slope of the best-fit line, with heteroskedastic-robust standard errors in parentheses. The number of rental properties for each plot is 2,402.

Taken together, our findings paint a troubling picture. First, as expected, landlords of all sizes struggled with rental collection during the pandemic. However, small owners, who were more likely to have tenants in arrears prior to the pandemic and who have a smaller real estate asset base to help diffuse such losses, were significantly more likely to see rental revenues drop by 50 percent or more. This continued loss of revenue for our nation’s primary providers of lower-cost housing has real implications for the current and future housing stock.

Another source of concern is the fact that nearly one-third of landlords have been deferring maintenance at their properties. In the near-term, this implies reduced housing quality for residents, who are also likely spending more time at home. In the long-term, this may decrease the expected life of a given property, putting additional strain on an already limited rental housing supply. Further, in order to pay for eventual repairs, owners may choose to increase rents, making existing units less affordable. Increases in the sale of rental properties may add to renter instability if new owners are motivated to seek rent increases to offset the cost of repairs and maximize returns on their investments.

These dynamics suggest an opportunity for policymakers to help support landlords while also preserving the privately-owned affordable rental stock. For example, public programs that provide funding to repair and improve the quality and energy efficiency of existing units can be connected to requirements to preserve their affordability for years to come. In cases where owners are looking to sell, local governments can develop tenant purchase options and/or facilitate the sale of properties to socially responsible parties looking to make the requisite property investments and commit to maintaining units as affordable.

Policymakers must also take steps to address the punitive measures—evictions chief among them—that owners are disproportionately pursuing in communities of color. Tenant supports and legal protections are critical, but these alone will not correct the persistent racial inequities in our housing markets. Affirmative federal and local commitments to further fair housing, as well as to communities of color well beyond the pandemic, are essential to address long-standing racial disparities in access to good quality, affordable housing. And finally, while there is a clear need for policy solutions that support owners, it is critical that they are not pursued at the expense of vulnerable renters doing all they can to remain housed.