Where Have All The Renters Gone?

After more than a decade of strong growth, the number of renter households in the United States fell in 2017, according to the three government surveys that track household formation. Specifically, the latest 1-Year American Community Survey (ACS) estimates from the Census Bureau indicate that the number of renter households dropped by 459,000 from 2016 to 2017 (from 43.84 million to 43.38 million households). Somewhat similarly, the Housing Vacancy Survey (HVS) showed a decline of 129,000 in that time while the biannual American Household Survey (AHS) found that the number of renter households declined by 111,000 between 2015 and 2017.

What is causing this decline and what might it mean for markets?

Is it due to a drop in new households being formed by young adults, who are most likely to become renters? If so, this could signal that the demand for rental housing is falling and/or that rental affordability is a growing barrier to establishing a household. Alternatively, could the decline in renter households be due to an increase in first-time homebuying? If so, that might be a sign that many young renters whose homeownership aspirations have been delayed are now finding it possible to buy rather than to rent, which might also reduce the upward pressure on rents. Or is the decline due to something else altogether, such as the aging of the population, which could result in rising numbers of renter households lost each year due to mortality or moves into nursing homes.

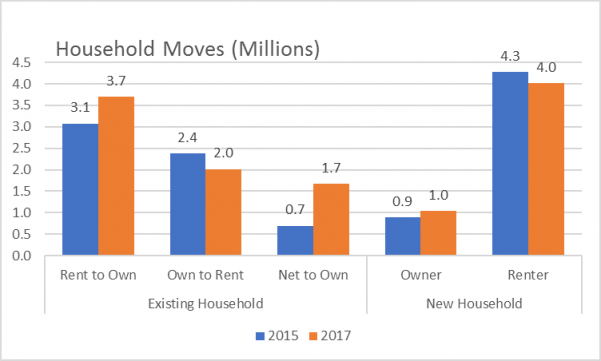

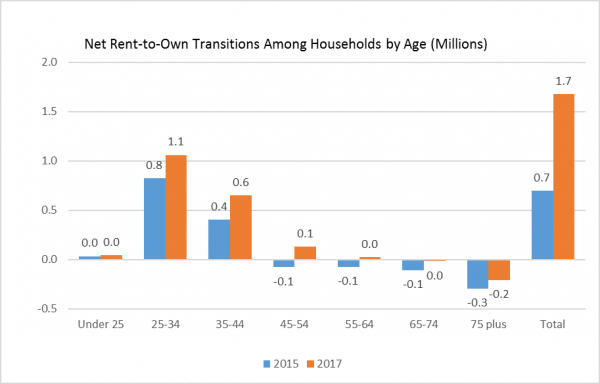

The AHS, which asks people who moved since the last survey whether they owned or rented their previous home, can help answer these questions. It suggests the major factor behind the loss of renter households is an increase in the number of renters switching to homeownership. Notably, compared to the 2015 AHS, the 2017 survey shows a 20 percent increase in the number of renters who moved into homeownership and a 15 percent decrease in the number of owners who moved into rentals. As a result, among existing households, there was a net shift of 1.7 million households from renting to owning, a more than three-fold increase from 2015, when, on net, only 0.7 million existing households moved from renting to owning (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The 2017 AHS Shows a Pickup in Renter Households Moving to Homeownership

Note: Excludes non-cash renter households

Source: JCHS tabulations of American Housing Survey data.

Figure 2: AHS Shows Net Transitions to Ownership Increased Most Among 25-44 Year Old Householders But Also Extended into Older Age Groups

Note: Excludes non-cash renter households

Source: JCHS tabulations of American Housing Survey data.

In addition, AHS also showed a slight decline in the number of newly formed renter households in 2017 relative to 2015 and a modest increase in the number of newly formed households that went directly to homeownership. Indeed, while the vast majority of newly formed households are renters, and the total number of moves among newly formed households held at just over 5 million in 2017, the number of those newly formed households that were homeowners grew by about 16 percent (from 900,000 in 2015 to 1.0 million in 2017), while the number that were renters dropped by six percent (from 4.3 to 4.0 million).

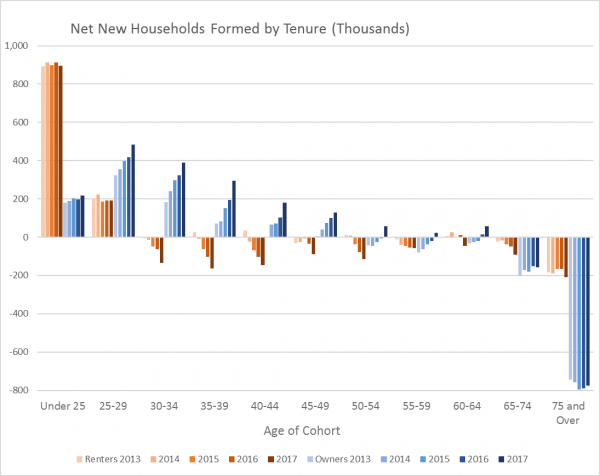

ACS data also suggest that increased transitions to homeownership among renters age 30 and over —rather than a decline in new renter household formations — is the primary cause of the decline in renter households. This data show that losses of renter households among households age 30 and over have increased in the past 3-5 years, while renter growth among younger cohorts held consistent (Figure 3). Additionally, on net, the number of homeownership households has increased for cohorts of those age 25 and over each year since 2013. (This, in turn, helped increase homeownership rates for the 25-34 and 35-44 year old age groups as documented in our 2018 State of the Nation’s Housing report.) The data also show that net losses of renter households among renters age 75 and over have remained stable, suggesting that an increased rate of losses due to the mortality of a growing aging population is causing the recent drop in renter households.

Figure 3: Younger Adults Are Still Adding on Similar Numbers of Renters, But Cohorts Over Age 30 Are Increasingly Losing Renters and Adding Owners

Source; JCHS tabulations of ACS 1-Year Estimates (averaged over 3 years to smooth volatility).

In sum, the decline in the number of renter households as measured in the three major Census Bureau household surveys over the past year does not appear to be due to a drop in new demand, as the number of net new renter household formations among the youngest households remains level. Instead, it appears to be driven by a surge in the number of renter households headed by people in their 30s and 40s transitioning to homeownership, a transition that has been less common since the mid-2000s.

Given that the renter households that are transitioning to homeownership have above-average incomes, this dynamic seems likely to contribute to a softening in high-end rental markets (which was also documented in this year’s State of the Nation’s Housing report. Moreover, it could have the potential to reduce pressures that drive increases in rents, which have continued to rise, albeit at somewhat slower rates than in previous years. And if rent increases slow (and incomes continue to rise) there may also be more units affordable for the many younger, less affluent people who are forming (or want to form) renter households in the next few years.