Where Are All the Homes? Demographic Underpinnings of the Lack of For-Sale Inventory

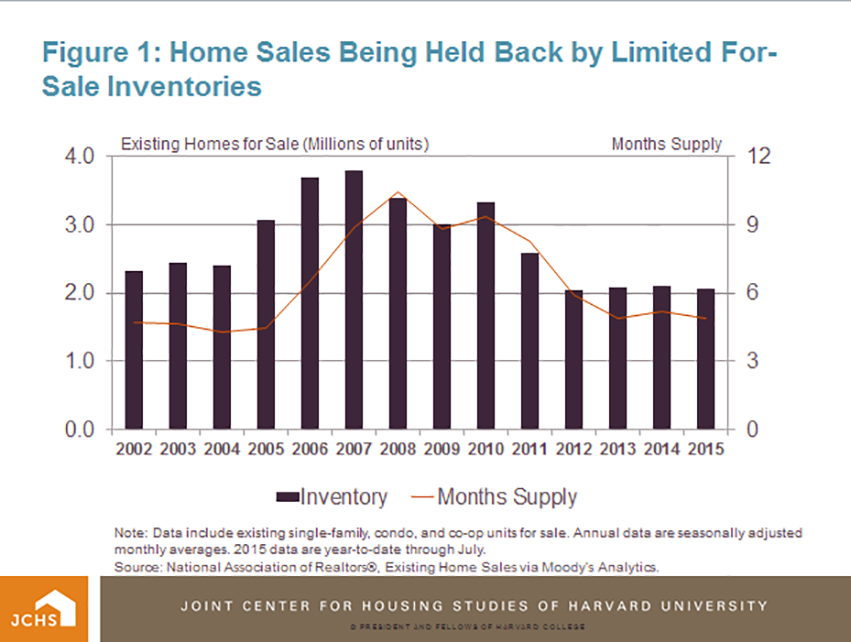

One of the challenges faced by housing markets has been a persistent lack of inventory of homes for-sale. Indeed, the most recent data on existing home sales from the National Association of Realtors® show that for 37 months we’ve been in a seller’s market – traditionally defined as a market in which there is less than six months’ supply of homes listed for sale (Figure 1). And, according to Redfin, this year’s spring buying season saw inventory nationwide hit record lows (see June Housing Markets Sets All-Time Records for High Speed and Low Supply). In the many markets with few homes available for sale, new listings are almost immediately snatched up, with the high competition among buyers pushing prices out of reach of a growing number of would-be homeowners.

Source: National Association of Realtors®, Existing Home Sales via Moody’s Analytics.

There are several possible explanations commonly mentioned as to why for-sale inventories remain so tight, including the large number of owners stuck in homes because they are ‘underwater’ on their mortgages, the still-elevated volume of homes in the foreclosure process and held off the market, the lack of new construction in the years following the housing boom, and the many single-family units that have been taken out of the for-sale market to become rentals. But one additional reason not often discussed is demographics, which has also been playing a role in both the lack of inventory and in the slowness in new home sales over the past several years. Indeed, the ongoing generational shift among American households has slowed sales in the short run and is likely to continue to dampen sales over the next two decades.

Demographics and the Reduced Pool of Active Trade-up Homeowners

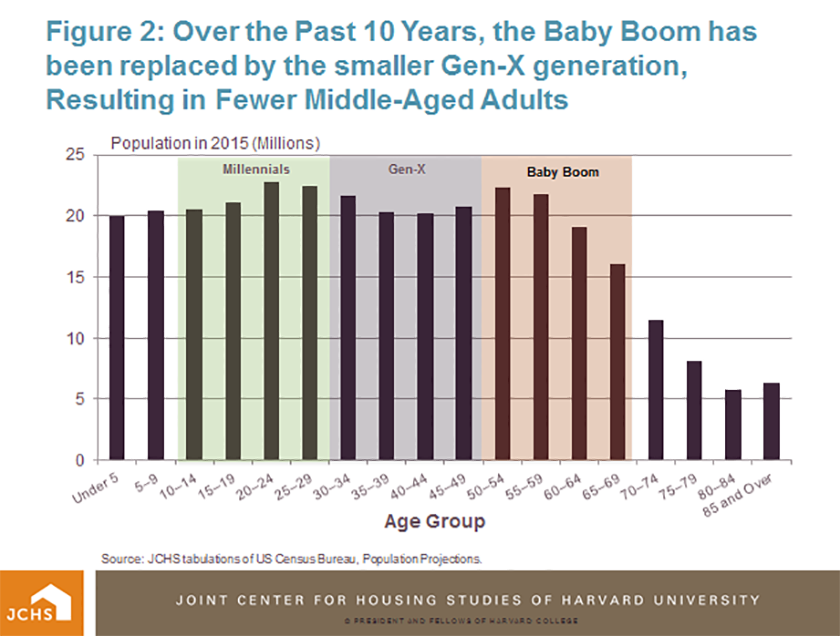

Over the past ten years, members of generation-X aged into the 30- and 40- year old age groups (Figure 2). As this relatively small generation, once called the baby-bust, replaced the large baby-boom generation now in their 50s and 60s, the population in their 30s and 40s declined. In some cases, the declines were stark. For instance, for the 35-39 year old age group, the population in 2013 was 9.3 percent smaller than it was 10 years earlier, with 10.4 percent fewer households.

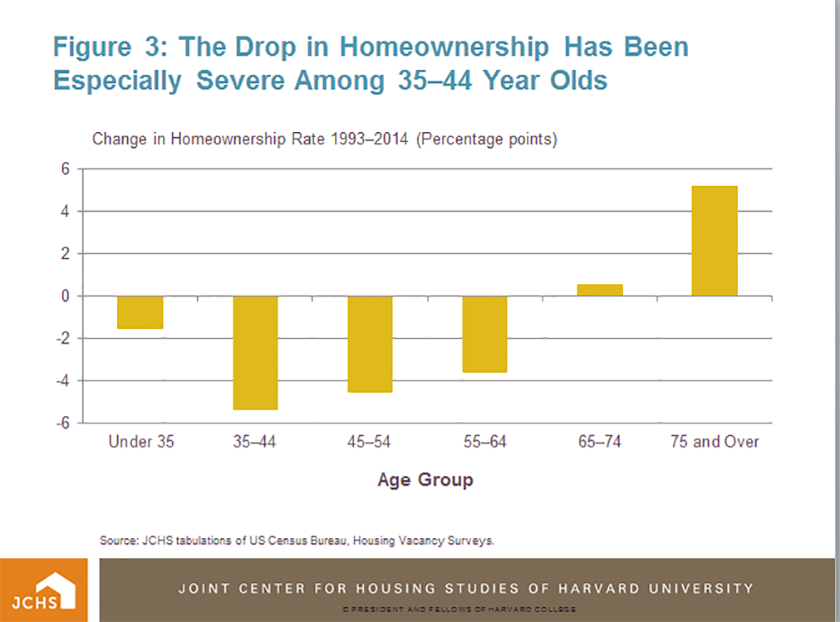

At the same time, as the 2015 State of the Nation’s Housing report mentions, the US homeownership rate took a significant dive, dropping to levels not seen in 20 years, with outsized declines among some age groups and the sharpest drop occurring among 35-44 year olds. Indeed, despite all the attention given millennials, homeownership rates among gen-Xers – particularly those currently age 35-44 – are actually furthest below 20-year historical rates of similarly aged adults (Figure 3).

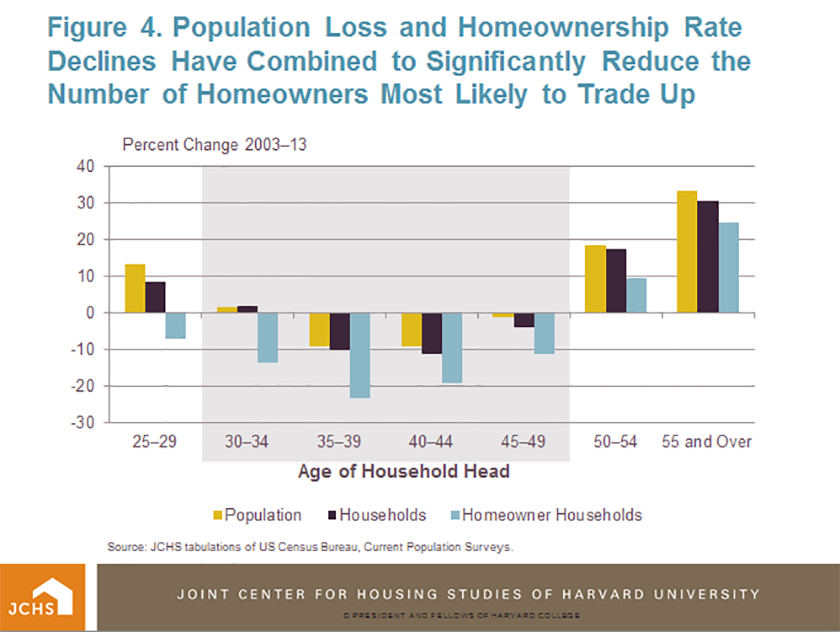

So in combination, the demographically-driven decline in population of 30- and 40 year-olds was magnified by a sharp drop in homeownership rates, resulting in a significant decline in the number of homeowner households at these ages. Among the 35-39 year old age group, for instance, the number of homeowner households dropped fully 23 percent between 2003 and 13, and among 40-44 year-olds the decline was a substantial 19 percent (Figure 4).

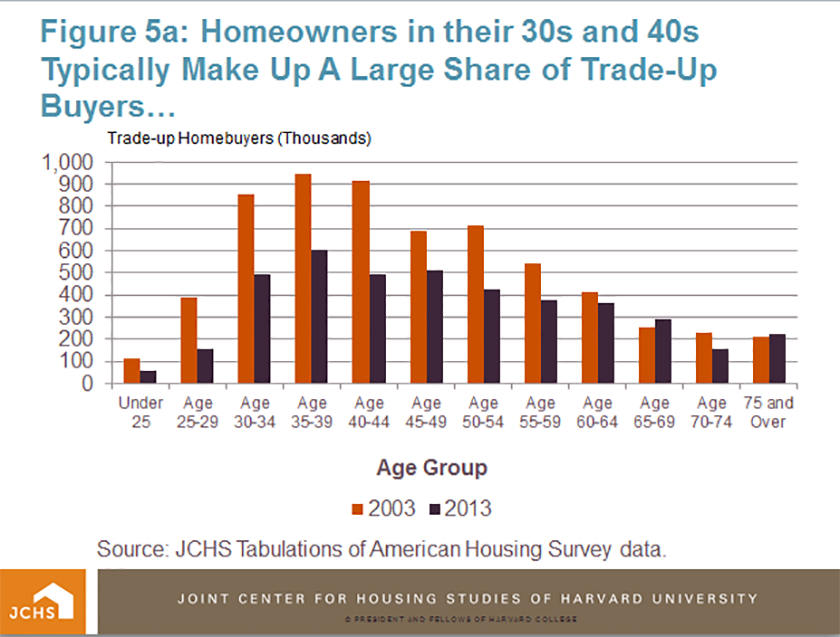

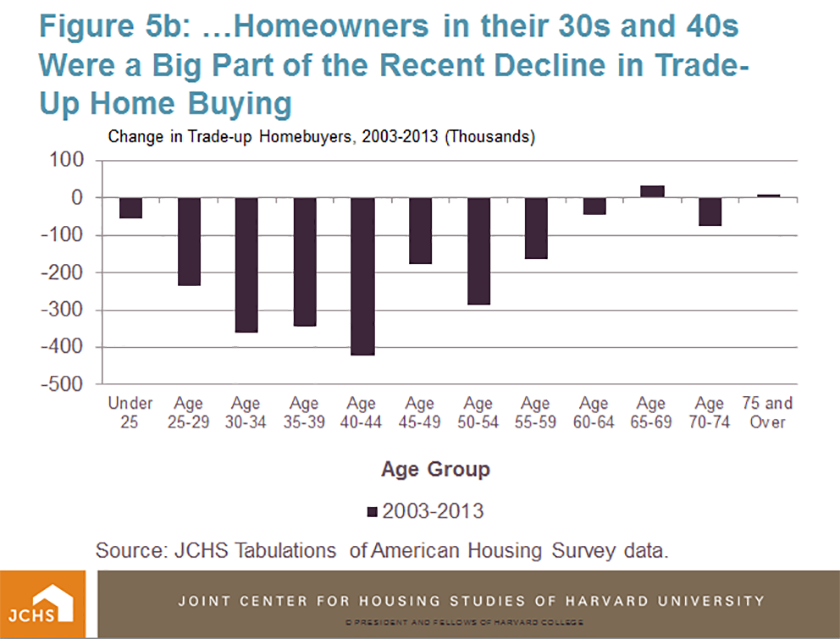

Traditionally, the 30s and 40s are key ages for housing market activity – particularly for trade-up and new home purchases. Indeed, homeowners aged 35-44 historically make up the majority of trade-up buyers (Figure 5). Fewer current homeowners in this key age group has meant fewer potential trade-up buyers and sellers, meaning fewer people putting their homes on the market, adding to tight inventories of for-sale homes.

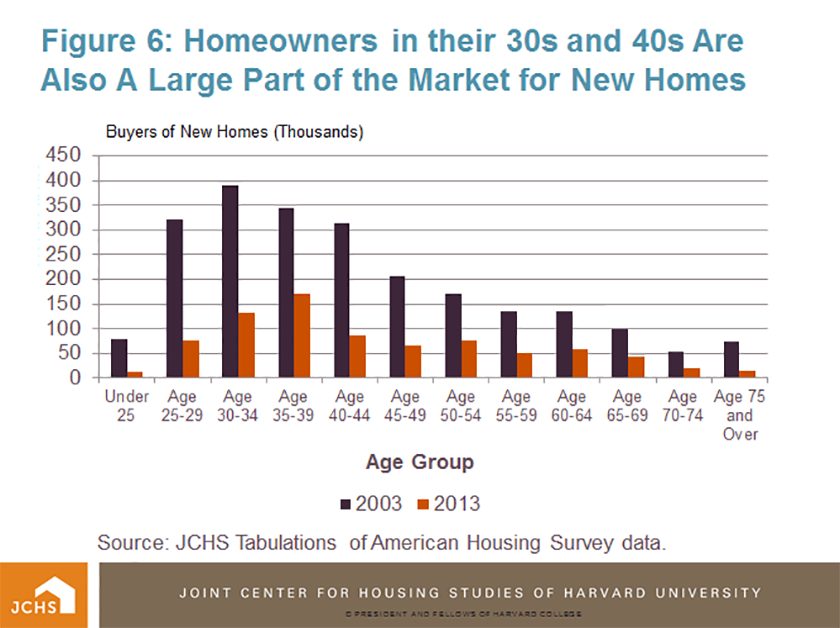

Additionally, one of the most common ownership opportunities desired by trade-up buyers is a new home. Indeed, 35-44 year olds are also typically responsible for a high share of new home sales (Figure 6). And the majority of new homes sales to this age group are to those who are currently homeowners, so fewer current owners in this age group has also meant fewer potential buyers of new homes, fewer new home sales, and therefore a sizeable headwind to single family homebuilding. And there are other implications as well, such as for home improvements spending, given that most movers do some kind of post-move improvements, even if it’s just painting the walls, so fewer sales among gen-X has also affected remodeling spending markets as well.

While the millennials and baby boomers attract most of the headlines about how demographic trends are influencing housing demand, gen-X ers may actually be more influential than they get credit for in contributing to the recent weakness in single-family construction, home re-sales activity, and the widespread lack of inventory in many markets.

One final note, however, is that the aging of the baby boom generation may also be contributing to the low levels of inventory and slower home sales – and this contribution may be a longer-lasting trend than that of the gen-X discussed above. Since mobility rates decline with age, the aging of the baby-boom will mean increasingly higher shares of older households who move less frequently. While there are concerns, most notably expressed in Dowell Myers’ insightful book Immigrantsand Boomers, regarding the potential future problem of elderly baby-boomers unloading a glut of housing on the market as they sell off or otherwise cease to head their own households, the oldest boomers are still only in their late 60s and so mostly many years from exiting the housing scene. And if for-sale inventories continue to remain tight as they are today, we may need to worry about the opposite problem: not enough turnover in the housing market to meet the needs of younger households, at least until boomers do reach the ages when they begin to vacate their homes in significant numbers. At present, it’s still hard to tell how much of the currently tight inventory is due to lingering effects of the housing downturn from longer term demographic shifts. Time will tell.