The Number of People Living Alone in Their 80s and 90s is Set to Soar

Over the next 20 years, the number of people in their 80s and 90s living alone will dramatically increase. Because those living alone at older ages can have greater needs for support in the home as well as fewer resources than similarly-aged couples, the growth in single-person households has implications for family members and policymakers alike.

The first baby boomers will reach age 80 within the decade. By 2038, there will be 17.5 million households in their 80s and over, more than double the 8.1 million in 2018. These households will also constitute an increasingly larger share of all US households, doubling from 6 percent in 2018 to 12 percent in 2038. As we note in our recent report, Housing America’s Older Adults 2019, the majority of these households will be made up of just a single person.

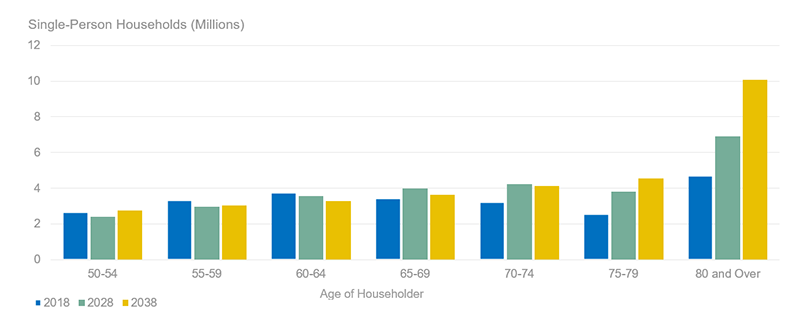

Most households headed by someone age 65 or over are either married couples living by themselves (37 percent) or single individuals (42 percent). With age, however, the share of solo households increases, reaching 58 percent among those 80 and over. As the baby boomers cross into their 80s over the next 20 years, the numbers of single-person households among the oldest age group will grow dramatically, from 4.7 million households in 2018 to an estimated 10.1 million in 2038 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: By 2038, The Number of Older Households Age 80 and Over Is Projected to Reach 10.1 Million

Source: 2018 JCHS Household Projections.

Currently, the majority of older single-person households are female; in 2018 women comprised 74 percent of solo households age 80 and over. While the gap in longevity between men and women has been narrowing, we can expect that over the next two decades, there will still be more women than men over 80 living alone.

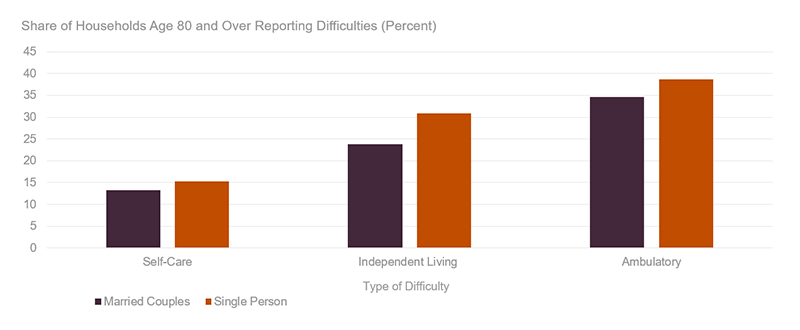

Single people in the 80-and-over age group have some unique needs. First, these individuals are more likely to report difficulties with mobility (walking or climbing stairs), self-care (bathing, dressing, and getting around the home), and independent living (conducting errands such as shopping or visiting a doctor) than those of the same age living as couples (Figure 2). In part, these shares may differ because the presence or absence of difficulties (particularly those related to independent living), as well as their extent, can be related to one’s living environment and household configuration. For example, if one member of a couple shops on behalf of both people, the other might not report a difficulty with that particular activity, though that same person might report it difficult if living alone.

Figure 2: Single-Person Households Are More Likely to Report Difficulties with Self-Care, Independent Living, and Mobility

Note: Married couples do not have any other household members.

Source: JCHS tabulations of American Community Survey 2018.

Not surprisingly, single people are more likely than other household types to pay for in-home assistance – or to go without the support altogether. Yet they also have lower median incomes than their married counterparts. People age 80 and over who live alone had a median income of $22,200 in 2018 compared to $51,700 for married couples.

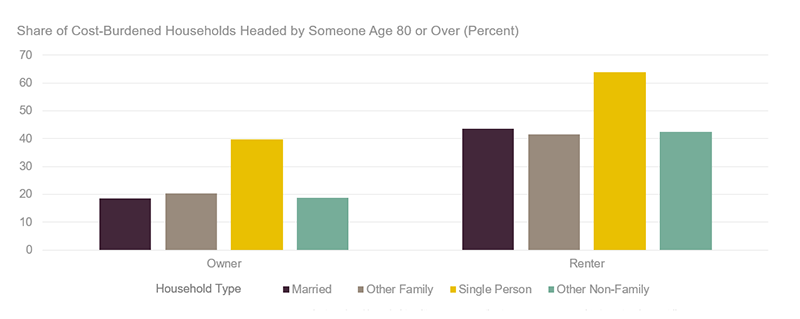

Lower incomes make it more difficult to afford housing, and single-person households are indeed more likely to face housing cost burdens (paying more than 30 percent of one’s income on housing) than those in other living situations. Indeed, single people age 80 and over are more than twice as likely to face cost burdens as married couples of the same age: while 22 percent of couples are cost burdened, single-person households are cost burdened at a rate of 48 percent.

Single persons are also more likely to rent their homes than married couples: just under half of owner households age 80 and over are made up of a single person, compared to 77 percent of renter households of the same age. Renting can have many benefits that older adults seek, including more accessibility features and less maintenance than an owned home. However, renters are more vulnerable to changes in housing costs and tend to have far fewer assets, including a home whose equity can serve as a cushion or source of income later in life. Renting is also more expensive than owning one’s home without a mortgage. For these reasons, nearly 64 percent of solo renters age 80 and over are cost burdened, compared to 18 percent of couples who own (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Single-Person Households Are More Likely to Face Cost Burdens

Notes: Cost-burdened households pay more than 30 percent of income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to have burdens, while households paying no cash rent are assumed to be without burdens. Married couples in this analysis do not have other household members.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2018.

Finally, older single people living alone are more likely to express that they are lonely, which itself is a risk factor for a host of adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Living alone does not itself cause loneliness, and older people living without a spouse/partner but with others also face higher risks for loneliness than couples. Yet for those dwelling solo, social engagement in the community may be especially important.

Going forward, all levels of government will need to address the needs of older adults living alone, particularly those who require in-home services and who live in places where social connections are made more challenging by limited transportation options. Technology may be able to help on both the social side and in providing help with household tasks – but much remains to be studied about technology’s potential to influence health and address loneliness, particularly among a group with limited financial means.

The growth of the nation’s older population presents opportunities for people to live healthier longer, and in the places and situations they choose – but only if informed by a clear view of the challenges and with concerted efforts to address mismatches in our aging population; the affordability, location, and suitability of our housing; and the availability of supportive services. This will be particularly true for the growing number of solo households in their 80s and beyond.