Surge in New Rental Construction Fails to Meet Need for Low-Cost Housing

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2013 American Housing Survey.

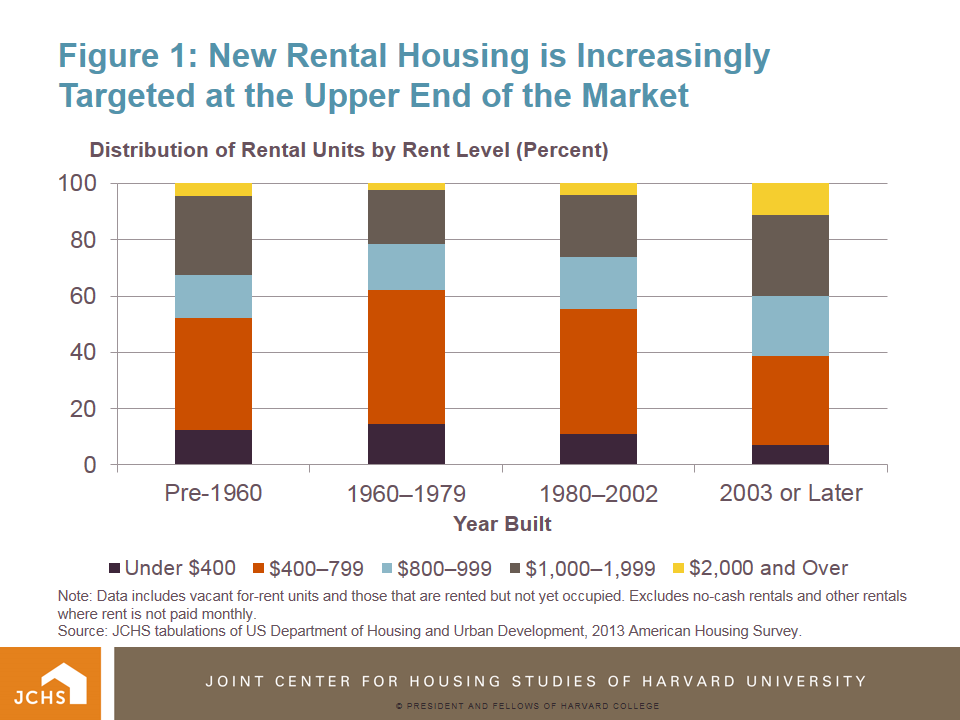

As we highlighted in our recent America’s Rental Housing report, the housing affordability crisis has shown little signs of abating in recent years, as renter incomes continue to lag behind rising housing costs. Though there has been a ramp-up in rental housing construction, much of this new housing is intended for renters at the upper end of the income spectrum (Figure 1). Indeed, in 2013, four in ten new rentals charged monthly rent of at least $1,000, compared to less than a quarter of rentals built during the heavy volume of multifamily construction in the 1960s and 1970s, which was largely supported by federal subsidies. In addition, the median asking rent for new market-rate apartments has been rising in recent years, reaching $1,372 in 2014, up by more than a quarter from 2012.

New construction is providing relatively fewer rentals that are affordable to those with lower incomes. According to the American Housing Survey, new construction increased the total number of units renting for $800 and over by 14 percent between 2003 and 2013—roughly triple the gain in the number of units renting for under $400. In fact, just 34 percent of rental housing built between 2003 and 2013 rented for under $800 in 2013.

Indeed, there is a mismatch between the type of rental housing built over the past decade and the needs of growing numbers of lower-income renters. Between 2003 and 2013, the number of low-income renter households who could only afford units renting for under $400 (at the 30 percent of income threshold) increased by 40 percent but the number of rental units affordable to these households rose just 10 percent on net. Most of this 10 percent increase came from the downward filtering of higher-cost units to lower rents, rather than the construction of new lower-cost units.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2013 American Housing Survey.

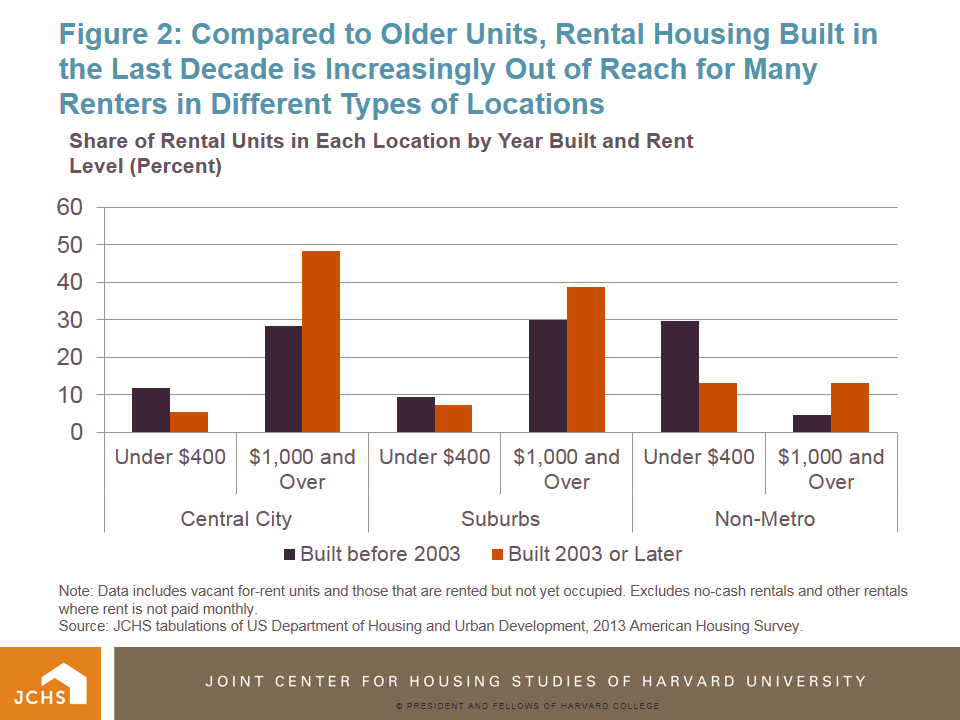

Rental housing built during the last decade is increasingly out of reach for many renters. This is true across the metropolitan region. In central cities, nearly half (48 percent) of new units rented for at least $1,000 a month in 2013, in contrast to just 28 percent of rentals built before 2003. On the other hand, while rentals in non-metro areas tend to include a higher share of the lowest-cost housing (units renting for under $400) relative to those in metro areas, new rentals built in these locations are much less likely than older rentals to charge rents this low (Figure 2). For example, only 11 percent of single-family rentals built in non-metro areas before 2003 rented for $1,000 or over in 2013 but this share rises to 53 percent of single-family rentals built in 2003 or later.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2013 American Housing Survey.

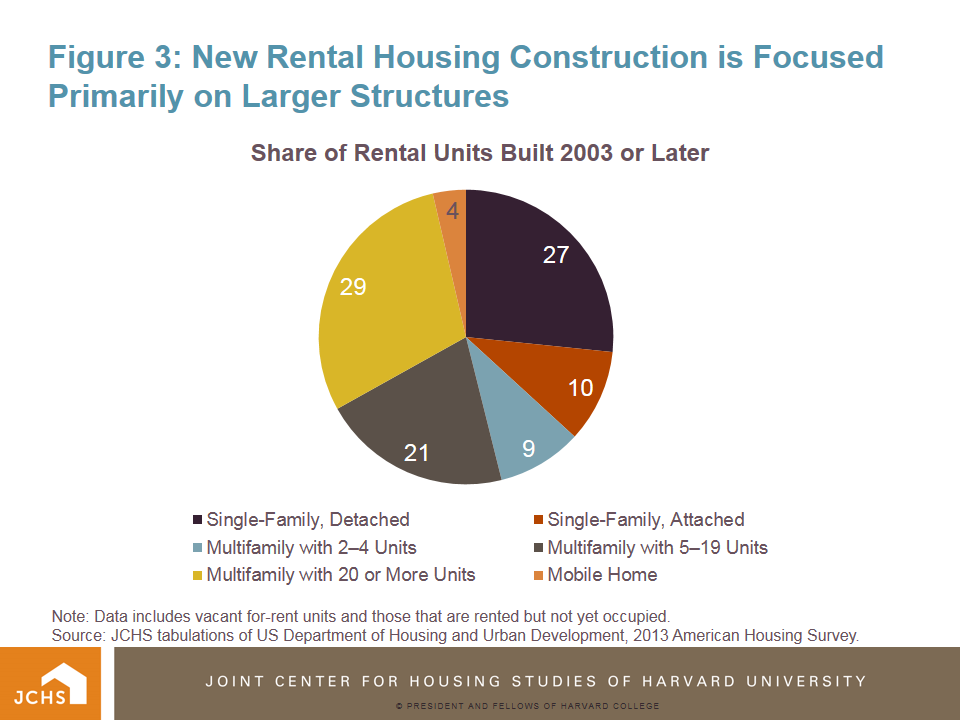

New construction has also tilted toward larger buildings. At least eight out of 10 apartments (84 percent) completed for rent in 2014 were located in properties with 20 or more units. This is well above the average share—62 percent—of new rental additions in the previous decade (between 1999 and 2009). With developers prioritizing the construction of units in large multifamily buildings, the addition of units in smaller buildings with 2–4 apartments has slowed significantly. Apartments in structures with 2–4 units fell from 20 percent of multifamily completions in the early 1980s to just 3 percent in 2014. And according to the 2013 American Housing Survey, units in small buildings with 2–4 units represented just 16 percent of multifamily rentals built between 2003 and 2013, and just 9 percent of all rental units built over this time period (Figure 3). In contrast, apartments located in multifamily buildings with at least 20 units made up the largest share of new construction—29 percent—during the past decade, followed closely by single-family detached rentals.

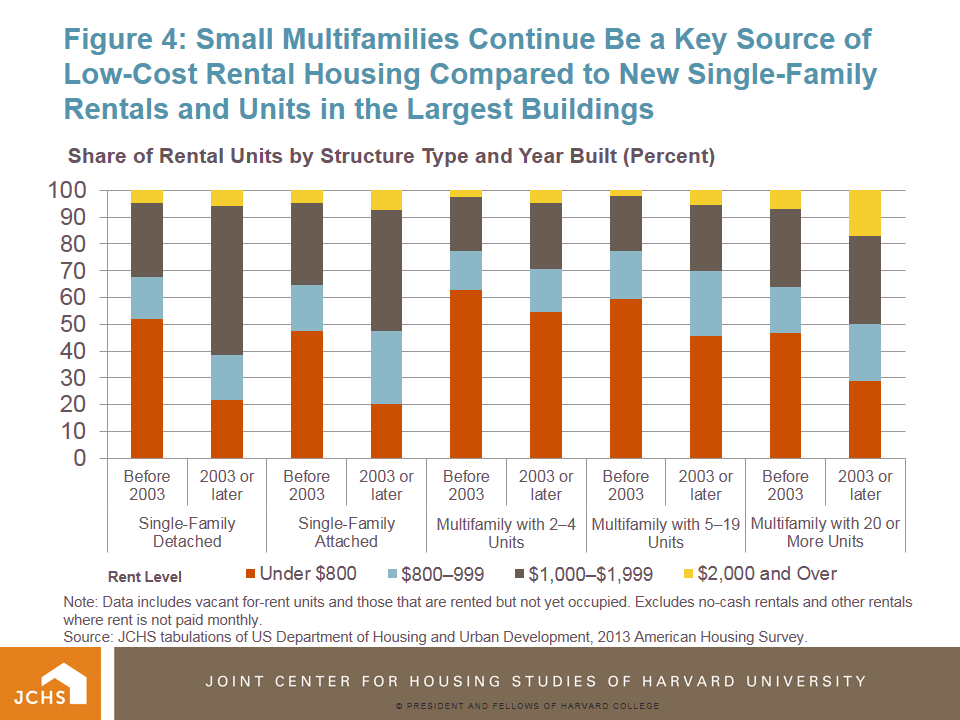

This decline in the number of new rentals in small buildings with 2–4 apartments is concerning given that units in these structures are typically more affordable than those located in larger buildings. In 2013, 63 percent of units in buildings with 2–4 apartments rented for under $800 a month, compared to 44 percent of those in buildings with 20 or more apartments. The age of rentals in the smallest multifamily buildings may help explain why these units tend to be more affordable than those in larger buildings. They tend to be older, with 44 percent of rental units in the smallest multifamily structures built before 1960, compared to less than a quarter of units in buildings with at least 20 units. However, even when accounting for units built in 2003 and later, those in buildings with 2–4 apartments are still more affordable than those in larger buildings. Over half (55 percent) of new rentals located in multifamily buildings with 2–4 apartments rented at under $800 in 2013, compared to just 29 percent of units located in buildings with 20 or more units that charged rents this low (Figure 4).

Although rentals in smaller structures with 2–4 units have also remained a key source of low-cost housing, they are also at higher risk of loss. In addition to their age, units in smaller multifamily buildings are more vulnerable to being removed from the affordable stock because they tend to be owned by “mom and pop” investors—typically an individual or couple—who have narrow operating margins due to high property taxes, heavy debt loads and inadequate cash flow. As this 2009 Federal Reserve Bank of Boston report notes, many of these mom and pop landlords hold other jobs that account for most of their earned income and are less likely than owners of much larger buildings—a group that is often comprised of partnerships, real estate investment trusts or corporations— to make an operating profit from their buildings.

A number of barriers exist to developing rental housing at a price point ($875) that the typical renter can afford. At the local level, developers may be faced with land-use regulations that restrict the area available to build multifamily housing as well as the number of units in these developments. These limitations can result in higher per-unit construction costs that are also passed down to tenants in the form of higher rents.

What can be done in order to build housing that low- and moderate-income households can afford, including units near transit-accessible, amenity-rich locations? A recent Urban Land Institute report has suggested that local governments offer publicly owned land at reduced or no cost to developers in high-cost metros such as Washington, D.C., and co-locate affordable housing developments with new public facilities such as libraries or community centers. Local inclusionary housing programs can also facilitate the development of affordable new units, but the amount of affordable housing developed through these programs is small relative to the volume produced through federal subsidy programs like the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program and HOME. In a 2010 report, the Innovative Housing Institute surveyed 50 inclusionary programs across the U.S. and estimated that they had produced more than 80,000 units since adoption. In contrast, over 2 million affordable rentals have been developed through the LIHTC program and 463,000 units through the HOME program to date.

Last month, Congress approved an appropriation of $950 million in funding for HOME in FY 2016, $50 million above the FY 2015 enacted level. Although this boost in funding represents a dramatic reversal from previous House and Senate proposals that had called for steeper cuts to HOME, the FY 2016 appropriation is still 56 percent below the FY 2006 level. Indeed, the strained fiscal climate may continue limit the availability of subsidies that make it economically feasible for both for-profit and nonprofit developers to build affordable rental housing.