The Incorporation of New Cities Has Increased Racial Segregation in Metro Atlanta

Racial segregation and the unequal allocation of resources have long shaped American cities, through a history of both overt and subtle racist policies and practices. While segregation persists today, it is also shifting locations: communities on the outskirts of major cities have emerged as key sites of racial change. This blog, the first in a series of two, highlights how municipal incorporations are fostering new racial segregation in metropolitan Atlanta.

Municipal incorporations, or the creation of new cities in the US, have decreased in number over the last few decades but still take place in some regions that have unincorporated territory (nine states in the US are fully incorporated). New cities are often in suburban, unincorporated parts of metropolitan regions, particularly in Southern states. For instance, greater Atlanta has added eleven new cities since 2005 and some movements are still underway.

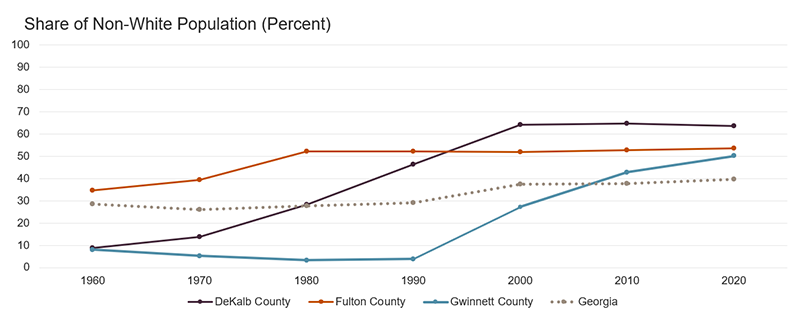

Most cityhood movements in Georgia have occurred in white, affluent communities in counties that have seen significant demographic shifts since the 1960s, particularly since 2000. In fact, the percentage of non-white people, most of them Black, in suburban Atlanta has significantly increased in all three counties with new cities, especially compared to overall trends in Georgia (Figure 1). It is important to note that the city of Atlanta seats in both Fulton and Dekalb counties. Geographically, Fulton is in the southern part of Atlanta, Dekalb east of the city, and Gwinnett is to the east of Dekalb. Other counties, such as Cobb county, which seats west of Atlanta, are just as populated as these counties but their populations largely consist of white people.

Figure 1: Georgia and Three Metro Atlanta Counties Have Seen Major Demographic Changes Since 1960

Work on incorporations pre-2000 has found mixed results with respect to the role of race in incorporation movements. Some research has found that incorporations were triggered by a genuine desire to protect home values, while other work has found that white communities used it to ensure racial exclusion. Luisa has studied cityhood movements since 2020 and has found that most recent cityhood leaders argue they want more control over land use and less redistribution of their tax money to other parts of unincorporated counties. Members of these newer movements generally avoid talking explicitly about racial issues when campaigning for cityhood but they often publicly seek more control over zoning and tax hoarding, which are tools that are often used to maintain residential segregation.

Figure 2 shows that 2020 median sale prices of homes in new majority white cities were higher than those in new majority Black cities and above the median of the counties they left behind. This indicates that regardless of what motivates these movements, by forming new pockets of government, white communities can have large impacts on the unincorporated areas they leave behind, which are often communities of color. Indeed, by detaching themselves from county governance, new cities take resources away from the common pool of unincorporated areas and can significantly hurt the economic development of these communities. These predominantly white, new governments separate themselves physically, fiscally, and politically from diverse communities.

Figure 2: Property Values in Majority White Cities Incorporated Since 2010 are Much Higher than in New Majority Black Cities and Higher Than Counties They Sit In

| Cities | Percent Black in New City | Median Sale Price in New City | Median Sale Price in County "Left-Behind" |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Majority White Cities | |||

| Brookhaven, Dekalb County | 11.6% | $500,000 | $280,000 |

| Peachtree Corners, Gwinnett County | 23.2% | $399,000 | $278,300 |

| Tucker, Dekalb County | 33.6% | $300,000 | $280,000 |

| New Majority Black Cities | |||

| South Fulton, Fulton County | 90.5% | $205,245 | $315,000 |

| Stonecrest, Dekalb County | 92.3% | $182,500 | $280,000 |

Importantly, left-behind communities may lack the political support and the economic means to push their own movements and create a new city. Even so, suburban Atlanta has seen some cityhood attempts and successes by Black communities. In fact, the newest three cities created in the area are majority Black enclaves: South Fulton, Stonecrest, and Mableton. Luisa has found in her research that Black leaders address different motives for incorporation compared to white leaders, including wanting to redress inequalities between new white cities and Black unincorporated areas left behind. Other work has also found that Black cityhood has been used as tool for social justice.

Unfortunately, even when communities of color are able to incorporate, research has shown that it is not yet clear whether they benefit or are hurt by their incorporation. In part, we know that white communities often are the primary beneficiaries of thriving material, spatial, and cultural community environments, ranging from best-resourced school systems to public transit access and tree-covered streets. Incorporation of Black enclaves may not change that.

Policymakers Have Tools to Mitigate Segregation and Promote Revenue Redistribution

Incorporation movements like those in Atlanta often result not only in heightened racial segregation, but, importantly, in tax revenue disparities between communities. Policymakers have several tools at their disposal, however, to address racial inequalities in cityhood movements. First, state legislators can strengthen and streamline requirements for incorporation, including allowing all county residents to participate in incorporation referenda. They can also require more in-depth assessments of the fiscal consequences to communities left behind by incorporations. In addition, to mitigate the detrimental impacts of incorporations, states can enforce stronger redistributive tax revenue policies, ensuring that communities with lower property values can also enjoy the highest quality schools and public services.