How Do Mortgage Refinances Affect Debt, Default, and Spending?

In the wake of the Great Recession, US monetary policy focused in large measure on purchases of mortgage-backed securities, with the goal of lowering mortgage rates. The resulting reductions in debt service payments were supposed to reduce defaults, increase consumer spending, and stimulate housing markets.

Despite the policy’s importance, to date there has been limited analysis of how the changes may have affected borrowers or how those effects differed among various types of borrowers. An important reason for this gap is that, because refinancing a mortgage requires an active, sophisticated financial decision, one cannot simply compare borrowers who refinanced to those who did not.

However, in a new paper, Andreas Fuster and I report on research that used a natural experiment created by the design of a federal program to examine how reductions in mortgage payments affected a broad set of financial outcomes for a variety of borrowers. We find that the reductions had large impacts on borrowers’ behavior and that the size and nature of those impacts depended on borrowers’ characteristics.

To understand the analysis, recall the mortgage crisis in the late 2000s. The meltdown in the housing market, and subsequently the broader economy, led to plummeting home prices. In response, the Federal Reserve aggressively pumped credit into the economy, which led to record-low interest rates for mortgages and other loans. The low interest rates meant that millions of American households with fixed-rate mortgages had strong incentives to refinance (to replace their existing, high-interest rate mortgage with a new, low-interest rate mortgage) but the collapse in home prices had left many homeowners with little or no equity, which meant they could not get new loans.

In 2009, the federal government responded to this problem by creating the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP), which allowed borrowers who had little or no equity in their homes to refinance their mortgages at lower rates. The program, however, was only open to borrowers whose initial mortgage had been guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac before June 1, 2009.

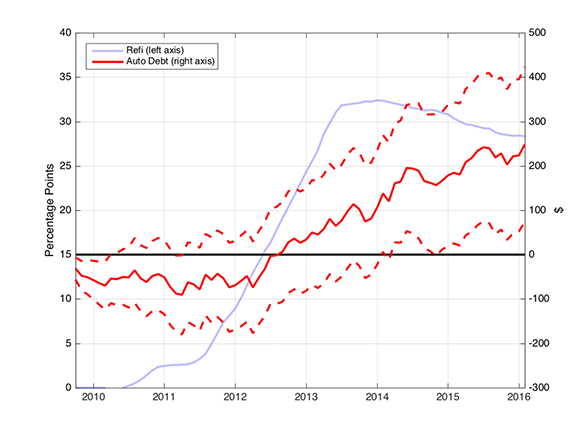

Our research took advantage of these features to compare borrowers whose mortgages were guaranteed just before this cutoff date to those whose mortgages were guaranteed just after. We found that HARP did, in fact, increase refinancing among eligible homeowners. Specifically, the light blue line in Figure 1 shows, month by month, how much more likely a borrower in the sample was to have refinanced their mortgage if they were in the eligible group versus being in the ineligible group. The key takeaway from that line is that, starting in late 2011, when the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates with its second round of quantitative easing, the eligible group became far more likely to have refinanced their mortgages, since they had access to HARP.

Figure 1. The Effect of HARP Eligibility on Key Outcomes

This shows the difference between the HARP-eligible and HARP-ineligible groups in their likelihoods of having refinanced (blue line, left axis) and accumulation of auto debt (red line, right axis). These differences are calculated while holding a host of other factors constant, as described in more detail in the paper (Figure 6 in particular). HARP eligibility is determined by the date on which a borrower’s mortgage was guaranteed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac; if this occurred before June 1, 2009, this eligibility requirement is met, and not otherwise.

Note: Chart corrected 5/21/19

The red line shows that borrowers used the savings on their mortgage payments to spend on other items, by looking at one particularly interesting outcome. Specifically, it shows the difference in the use of auto loans, which are a proxy for spending on cars, between the homeowners that were eligible and ineligible for refinancing under the HARP program. Before the refinancing boom in 2012, the eligible and ineligible groups did not differ significantly in their use of auto loans. However, coincident with their increased rates of refinancing, the HARP-eligible borrowers took out more auto loans, which indicates that they used the savings from the reduced mortgage payments to spend more on vehicles.

While that gives intuition for the approach, we quantified the impact of a refinance for many different outcomes using an econometric design described in the paper. We found that refinancing decreased mortgage defaults by about 40 percent and serious delinquencies on other types of debt by about 25 percent. Moreover, these results were driven almost exclusively by borrowers whose homes were most deeply underwater, and who had lower credit scores and lower levels of unused revolving credit. This suggests that for people who were struggling to make ends meet, the mortgage payment relief they gained from refinancing via the HARP program often was the difference between them being able to make their payments on their mortgages and other loans and not.

We also found increases in auto loans, home equity lines of credit, and other debts associated with spending of about 60 percent of the reduction in mortgage payments. Here again, the responses were stronger for struggling borrowers. However, we also found that many borrowers who had high levels of credit card debt responded to the lower mortgage payments by paying down these balances, a sensible response given the high interest rates associated with credit card debt.

The paper concludes by showing that, while struggling borrowers seemed to be most responsive to mortgage payment reductions, they also were less likely to refinance in the first place. It is difficult to say exactly why this was the case, but that key contrast heightens the importance of policymakers considering how to make programs such as HARP as easy to access as possible, so those who need them most can actually reap their benefits.