Greater Assistance Needed to Combat the Persistence of Substandard Housing

Earlier this month, Berks County, Pennsylvania was among the first jurisdictions in the state to open its doors to eligible households in need of basic home repairs. Pennsylvania’s Whole-Home Repairs Program is the first statewide initiative to subsidize home repair costs for lower-income homeowners and rental property owners, using $125 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds to address urgent concerns related to habitability, safety, accessibility, and weatherization. The effort is in response to the persistent issue of physically deficient housing; in 2021, 6.7 million US households, or 5.2 percent of all US households, lived in substandard homes with multiple structural deficiencies or lacking basic features such as electricity, plumbing, or heat.

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) developed the concept of physical adequacy to evaluate whether housing units met basic safety and suitability standards that were established in the Housing Act of 1949. HUD classifies housing units as moderately inadequate if they have three or four significant structural problems such as water leaks, large open cracks in the unit, or holes in the floor. Units are considered severely inadequate if they have at least five significant structural problems, an electrical problem such as exposed electrical wiring, or lack features such as hot and cold running water, a shower, a flush toilet, or electricity. Some research suggests that physical adequacy does not distinguish well among extremely low-quality units, and HUD’s analysis of this measure shows that many units that meet the criteria for physical adequacy have other physical problems that pose health and safety risks to occupants.

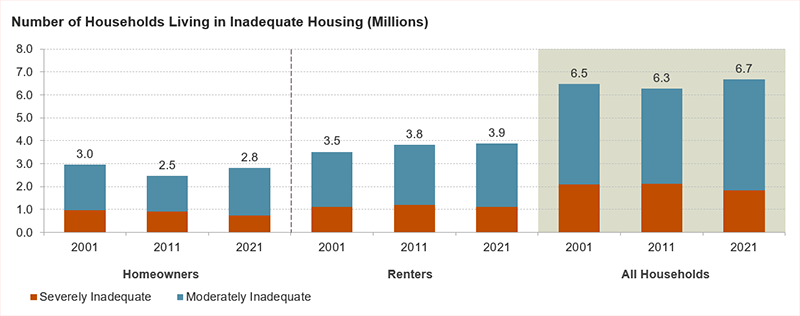

Despite improvements in building codes and construction standards, the number of US households living in substandard homes has remained largely unchanged over the past twenty years (Figure 1). According to analysis of the most recent American Housing Survey, in 2021, 2.8 million homeowner households and 3.9 million renter households lived in moderately or severely inadequate housing. And while the number of homeowner households in inadequate housing declined by 147,000 over these two decades, the number of renter households living in homes with structural deficiencies increased by 354,000. In total, 6.7 million households lived in inadequate housing, an increase of 206,000 since 2001.

Figure 1: Housing Inadequacy Remains a Persistent Problem for Homeowners and Renters Alike

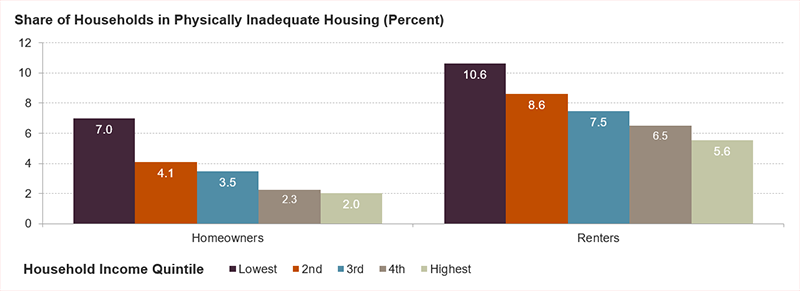

Unsurprisingly, households with lower incomes are the most likely to live in inadequate housing (Figure 2). In 2021, 7.0 percent of homeowners in the bottom fifth of household incomes (earning less than $24,000 per year) lived in homes classified as moderately or severely inadequate, more than three times the share of homeowners with incomes in the top fifth for incomes (earning $129,000 or more). Likewise, 10.6 percent of renters in the lowest income group lived in inadequate housing, nearly double the 5.6 percent share of renters in the highest income group. In total, households in the bottom fifth of incomes accounted for 34 percent of all households living inadequate housing in 2021.

Figure 2: Households with Lower Incomes Are More Likely to Live in Homes with Physical Deficiencies

Maintaining safe and suitable living conditions presents a distinct challenge for homeowners with lower incomes, many of whom lack the resources to remediate deficient housing conditions. As noted in our most recent Improving America’s Housing report and a blog I wrote last year, nearly half of lowest-income homeowners spend little or nothing for home improvement and repair projects. Lower income homeowners are far more burdened by home remodeling and repair costs and much less able to invest in needed repairs and updates. Renters also have little control over the physical conditions of their homes. As illustrated in books like Stacked Decks, low-income renters typically have limited housing options they can afford, and often the only housing available to them is poorly maintained.

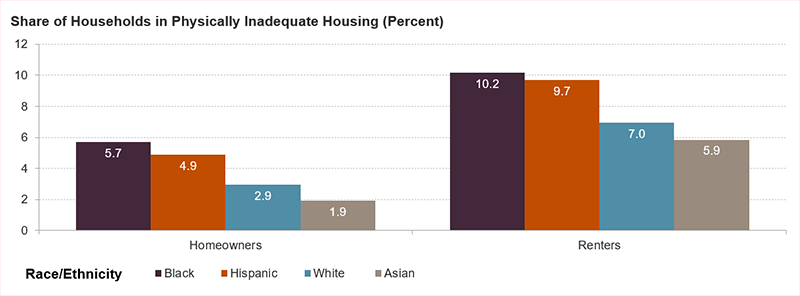

Among homeowners and renters alike, Black and Hispanic households were disproportionately likely to live in inadequate housing (Figure 3). Racial disparities in housing conditions reflect centuries of racially discriminatory policies and practices that have excluded households of color from neighborhoods and often limited their housing choices to those in dilapidating neighborhoods with declining property values. Even after the passage of the Fair Housing Act, discriminatory real estate practices such as predatory inclusion steered many Black homebuyers to neighborhoods with older and less adequate housing stock. In 2021, 5.7 percent of Black homeowners and 4.7 percent of Hispanic homeowners lived in moderately or severely inadequate homes, well above the 2.9 percent of white homeowners and 1.9 percent of Asian homeowners living in inadequate housing. And among renter households, Black and Hispanic renter households were more likely to occupy inadequate housing (at 10.2 percent and 9.7 percent) than white households (7.0 percent) and Asian households (5.9 percent). Racial disparities in housing adequacy persist even after accounting for household income. Among households in the bottom third of incomes, 10.4 percent of Hispanic households and 10.0 percent of Black households lived in inadequate housing in 2021, well above the 6.3 percent share for white households.

Figure 3: Households of Color Are Disproportionately Exposed to Physically Inadequate Housing

Addressing housing quality issues and remedying disparities in housing conditions will require greater public investment. Tens of millions of homes in the US have one or more critical home repair needs. A 2023 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimated the total cost of addressing physical deficiencies in the US housing stock at $149.3 billion, including $97.9 billion for the owner-occupied stock and $51.5 billion for the renter-occupied stock. While the investment needed to update the US housing stock to meet contemporary home performance standards is significant, an investment to ensure basic safety and habitability is smaller in scale, and within the realm of achievable housing policy.