The Evolving Landscape of Social Housing in New England: What We Learned

In mid-April, the Joint Center for Housing Studies brought together affordable housing developers, advocates, and policymakers for an event to reflect on the evolving landscape of social housing in New England. From Seattle to Atlanta by way of Chicago and Chattanooga, the growing list of new social housing programs attests to the urgent need for a different approach to the affordability crisis. These programs are a response to the record number of households across a broader range of incomes burdened by housing costs. Accordingly, they generally address both the scale and the scope of the need for affordable housing by increasing overall production and making more households eligible to live in this housing. So what does this nationwide movement mean for New England, a part of the country that is notoriously expensive yet uniquely rich in housing expertise?

Ida Kollins, age 6, from East Boston, left these and other notes on the podium during the event. In just a few words, she summed up some of the key principles guiding the nationwide social housing movement. Photo: Zak Davidson.

In his opening keynote, Massachusetts State Representative Mike Connolly, a champion of social housing on Beacon Hill, noted that social housing requires a conceptual rethinking of the larger US housing system: facilitating public investment in and ownership of housing that keeps public funding serving its purpose in the long term rather than allowing it to revert to market rates. Social housing would ideally allow moving beyond the country’s prevailing two-tiered housing system: income- and price-restricted housing, of which there is never enough, versus unrestricted market-based housing, which is increasingly unaffordable.

Most of the experts in the room had not considered their work to fall under the umbrella of social housing. Rather, they speak of public housing, affordable housing, or community development. And yet, much of what they do aligns with key principles of the new social housing movement. These principles include, first, a commitment to the permanent affordability of homes, or shielding rents or resale prices from market pressures; second, ensuring residents’ voice in a property’s design, operation, and long-term stewardship; and third, serving households across a broader range of incomes and backgrounds than existing programs allow. Low-Income Housing Tax Credit developments and housing vouchers are largely limited to renters earning less than 60 percent of area median income. The event was an opportunity for these practitioners to jointly explore how they could contribute to, and make use of, the current momentum to rethink the country’s housing system. In three panels, they discussed key strategies that have been advanced by social housing programs nationally: reinvigorated public development, new governance models, and innovative forms of financing.

Boston Housing Authority, in collaboration with Leggat McCall Properties, Charlestown Resident Alliance, Stantec, and Suffolk Construction, is redeveloping Bunker Hill Housing, a 1940s low-rise development in Charlestown. The project will replace 1,110 aging public housing units with a 2,699-unit mixed-income community and represents the largest public housing redevelopment in Boston’s history. Photo: Courtesy of Leggat McCall Properties.

The first panel, Enabling Public Development, considered if and how, after a half-century of underfunding and political delegitimization, the public sector can again assume a lead role in developing, owning, and managing housing. Kenzie Bok, administrator of the Boston Housing Authority, Deborah Goddard, secretary of the Rhode Island Department of Housing, and Margaret Moran, deputy director of development at the Cambridge Housing Authority (CHA), reminded the audience that housing authorities are the country’s existing public developers. Given their experience, including in recent redevelopment projects, and their long-term perspective in operating their assets, they have played a critical role in ensuring that desirable cities remain accessible to lower-income residents. The fact that the CHA is now advising 19 other housing authorities and co-developing with three attests to the fact that thinking big and building institutional capacity in the public sector is possible where there are political will and resources available.

The second panel, Empowering Residents, brought together Peter Fousek, secretary-treasurer of the newly-formed Connecticut Tenants Union (CTTU), the first statewide organization of its kind; Michael Monte, CEO of the Champlain Housing Trust in Vermont, the country’s largest community land trust; and Mary O’Hara, executive vice president of ROC Movement, a nationwide movement with origins in New Hampshire that assists manufactured home residents in converting their properties to cooperative ownership. While distinct, each of these organizations model how to give residents—whether renters or homeowners—a meaningful voice in how their housing is managed and operated. Residents are not only essential for building political constituencies, such as through a tenants’ union, but are critical for designing practical solutions. Citing one of ROC’s projects, O’Hara noted that residents often know best where to invest infrastructure money to maximum benefit; in one case, they chose a sheltered bus stop that became a meeting place for all. In other words, resident control and financial feasibility, according to O’Hara, go hand in hand.

Resident control can take a variety of forms. Left: CTTU members and allies rally in response to retaliatory evictions. Photo: CTTU. Right: Member-owners of a New England ROC vote on their annual budget. Photo: ROC.

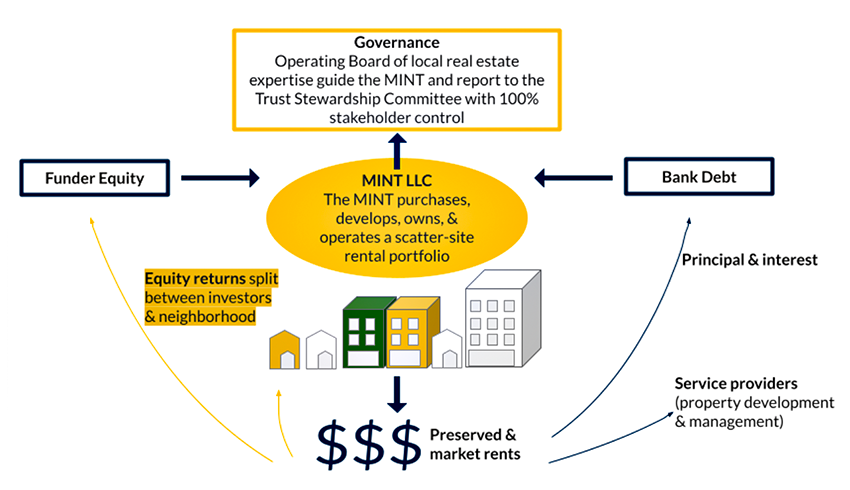

On the third panel, Expanding Financial Supports, Tanya Hahnel, project manager at the East Boston Community Development Corporation (EBCDC), Chrystal Kornegay, CEO of MassHousing, the state’s housing finance agency, and Craig Saddlemire, co-founder and cooperative development organizer at Raise-Op Housing Cooperative in Maine, discussed what is, perhaps, most central on everyone’s minds: money and the complexity and shortcomings of the current funding programs. On the one hand, Kornegay stressed that there is no shortage of private investment capital in real estate, but not enough is being channeled to affordable housing development—a low-risk proposition given current demand. Hahnel confirmed this sentiment by describing how private equity investors, albeit patient and socially motivated to support the EBCDC’s anti-displacement efforts, had made possible the acquisition of a portfolio of 114 apartments. It did so through a Mixed-Income Neighborhood Trust (MINT), a model that leverages private capital while still maintaining community control. On the other hand, the panelists stressed that current public sector investment for affordable housing is substantially lower than what is needed. In addition, the programs are highly restrictive, making it difficult to build anything other than standard apartment buildings. Saddlemire’s experience financing the new construction of a 16-unit group-equity cooperative with low-income housing tax credits—which he described as excruciating given that cooperatives do not fit existing underwriting criteria—was not one he was eager to repeat.

In 2023, EBCDC used a MINT model to purchase 114 apartments using public, private, and philanthropic funds. The MINT is accountable to neighborhood priorities through its governance structure. The portfolio is designed to preserve current rents ahead of pricing pressures raising rents. Image: Trust Neighborhoods.

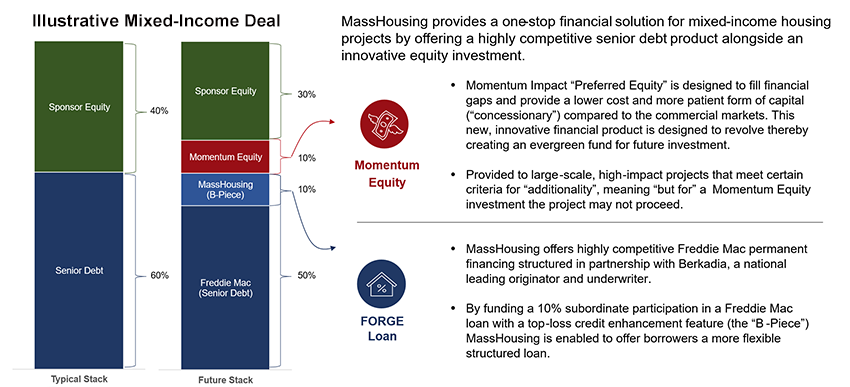

The conversations confirmed the convening’s hypothesis: that while the social housing movement is often presented as a new approach, many of its principles have been implemented throughout New England for years. First, making housing permanently affordable is doable and is being done. The state of Vermont has required this from Low-Income Housing Tax Credit developments since the early 2000s. Second, successful models for resident control abound. The Champlain Housing Trust’s tripartite board brings together the municipality, residents of their housing, and members of the broader community to oversee operations, which helps to balance various interests. CTTU uses collective bargaining to protect residents’ interests and fair rent. Third, new models of direct public investment, often in private sector development, secure some degree of permanent affordability and sometimes long-term public co-ownership. Examples include MassHousing’s BILD initiative, a revolving loan and equity fund launched in 2024. In other words, experimentation with and implementation of social housing principles is under way.

In 2024, MassHousing launched BILD, a revolving fund providing equity and loans to lower the cost of financing. At least one fifth of a development’s apartments must be affordable to households at or below 80 percent AMI. Image: MassHousing.

New England also shows that achieving scale is possible. CHA and Champlain Housing Trust each own and manage over three thousand homes that serve a broad range of household types and needs. But this scaling has been possible only thanks to the political and financial support of the respective municipalities and states over decades. It cannot be overstated that the potential of many smaller organizations, like Raise-Op, to provide new housing types and tenures, is held back by the lack of such support, specifically the severe lack of flexible and affordable capital.

CHA and Medford Housing Authority (MHA), as co-developers working with BH+A Architects, are completing the $105 million modernization of Saltonstall Apartments, a 1960s high-rise. The project converts the property to the Section 8 program and increases the site’s unit count from 200 to 222. The collaboration will bolster MHA’s ability to independently pursue development activity in the future. Photo: Chris Moyer.

The event’s rich and wide-ranging discussions did not delve into some of the fault lines within the social housing movement. The question of scope—or whether social housing is to serve a broader range of incomes than current programs—is fraught given the enormous need among very low-income households. The majority of models presented serve precise income brackets and set rent as a percentage of household income. Revolving loan or equity funds, such as MassHousing’s, rely on 70 to 80 percent market-rate homes to cross-subsidize roughly 20 to 30 percent below-market homes. In some ways, this perpetuates the existing two-tiered system and does little to truly expand the scale of affordable housing efforts. A similarly fraught question, whether individual wealth-building should be possible in social housing, was touched upon only indirectly. The Champlain Housing Trust strikes a balance. It subscribes to a continuum of opportunities—from the “safety” of shelter, to the “stability” of renting, to the “mobility” of owning—and limits individuals’ monetary benefit to 25 percent of the home’s appreciation through a shared equity model. The trade-off between the long-term public interest of maintaining affordability and residents’ interest in individual financial gain remains an outstanding question, but an urgent one in light of the enormous, and by some measures growing, racial wealth gap.

The closing panel asked Rep. Mike Connolly and Tufts professor emerita Rachel Bratt to reflect on the afternoon. Bratt is a longtime advocate for a robust community-based nonprofit sector and “quadruple-bottom-line” housing that takes into account social and environmental outcomes in addition to financial returns. She began her response with a frank admission: “I am distracted.” She was referring to a political climate that makes talk of social housing seem disconnected from reality. Still, she struck a proactive tone and reminded everyone that “this is the time to organize” to protect current programs and prepare for when the political climate shifts. Recent funding allocations for pilot projects in Rhode Island and Massachusetts are one way to test new models with an eye to the future. Connolly was more optimistic. He insisted that new efforts, in particular revolving loan funds, are important because even if only a fraction of the housing is affordable to lower-income residents at first, over time public co-ownership will lead to increased affordability. But he also cautioned that new revenue streams—including through progressive taxation—are needed if social housing is to be scaled.

At the conclusion of the event, what was clearest is that social housing is an opportunity to rethink the US housing system as a whole. The movement has articulated important principles, from resident protections to the need for a more proactive public sector, as well as a long-term perspective on the stewardship of housing. To seize this momentum, however, social housing must be framed as an extension of, not a threat to, existing efforts and funding sources. The for-profit and nonprofit organizations that have been the backbone of affordable housing provision for decades have not been vocal leaders in the social housing movement. This is likely due to a deeply ingrained scarcity mentality, leading them to expect more competitors vying for already-limited funding sources. This scarcity mentality prevents experienced actors from envisioning something broader and bolder, something that will address both the scale and scope of the housing crisis and move beyond the two-tiered system of the past. The panelists’ willingness to share their knowledge and experience with each other and with the audience, often with humor and personal anecdotes, attests to the fact that something new can emerge when experienced actors and relative newcomers can agree on a few fundamental principles.