Defining the Generations Redux

How should we define the baby boom, Generation X, and the millennial generation?

In a Joint Center blog published in 2012, I argued that using 20-year age spans for each generation would make it easier to compare them. Since many researchers still use generational definitions that span different and inconsistent age ranges, particularly for millennials, it is perhaps timely to reframe and restate my case.

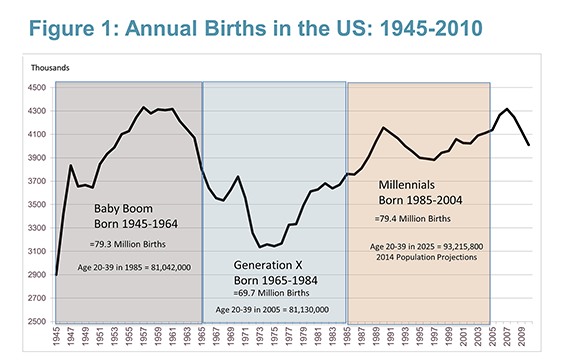

In keeping with my recommendations, the Joint Center has long identified the cohort born between 1945 and 1964 as baby boomers.Those born between 1965 and 1984 are Generation X, and the cohort born between 1985 and 2004 are millennials (Figure 1).

However, other analysts use several different earlier dates to usher in the millennial generation, apparently because they want to ensure that the oldest member of this cohort were considered adults at the dawn of the new millennium (i.e. they had turned 18 or 20 in the year 2000). This definition meant that by 2015, the oldest millennials were in their mid-30s, old enough to prompt compelling stories about how many 30-somethings were still living with parents, living in cities, forsaking marriage and childbearing, and delaying homeownership. In contrast, under my recommended cut-off dates, the oldest millennials turned age 20 in 2005 and didn’t start entering their 30s until 2015.

Besides making it easier to compare generations, there are several reasons why the millennial generation should start with those born in 1985 and turning 20 in 2005. As I noted in my 2012 blog, 1985 was the year that U.S. births once again exceeded 3.7 million, the approximate number that demarcated the beginning and the end of the baby boom, as well as the beginning and the end of the “baby bust” that defines Generation X.

Three other big changes occurred shortly after 2005 that significantly altered the way young adults live. First, social media participation skyrocketed. Facebook became available to everyone age 13 and older with a valid e-mail address in September 2006. Twitter became public in 2006. The first iPhone was released in June of 2007. As a result of these and other changes, the share of adults using social media rose from five percent in 2005 to 69 percent in 2016, according to a recent Pew Research publication.

Second, student loan debt outstanding more than tripled between 2005 and 2016, rising from $400 billion to over $1.3 trillion. This high level of debt is thought to affect everything from leaving the parental home, to getting married and starting a family, and purchasing a first home.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, the economic changes that led to the Great Recession hit hardest among young adults who were in their 20s shortly after 2005. The unemployment rate of adults older than 25 without a high school degree rose from below six percent in late 2006 to 15 percent in mid-2009. (Those with a high school degree or more followed this trend within a year.) Unemployment rates of those with a high school degree or more have slowly improved, but still remain above pre-recession levels. Unemployment rates for those with less than a high school degree have returned to their pre-recession elevated levels, but people in this group generally are making less money and receiving fewer benefits than they did before the recession. Meanwhile, housing costs have returned to, or now exceed, their pre-recession levels.

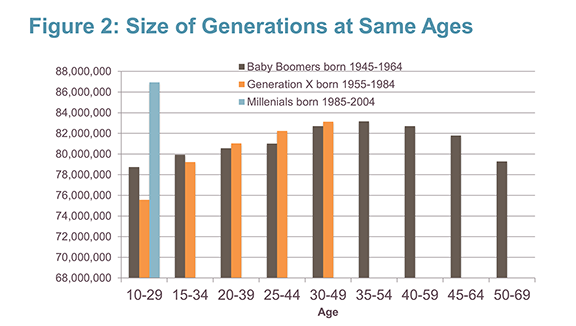

Using equally broad 20-year age spans produces several important findings about the different generations. To start with, the millennial generation has been larger than the baby boom generation, now or at any other previous time since the boomers were age 10-29 in 1975 (Figure 2). Millennials now number almost 87 million compared to less than 79 million for baby boomers at the same age. This is in contrast to findings of a 2016 Pew Research study that compared generations using millennials with a smaller age range and found roughly equal numbers between these two generations in 2015 (75 million).

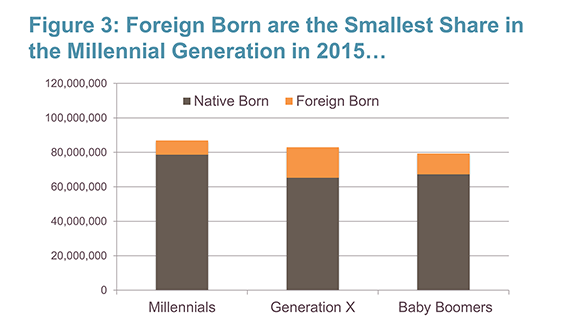

Using consistent age spans also shows the changing ways that immigration has affected the number of people in each generation. In 1995, when Generation X was age 10-29, it was smaller than the baby boom generation was in 1955, when it was the same age. However, because of immigration, by 2005, when Generation X was age 20-39, it already exceeded the number of baby boomers at the same age.

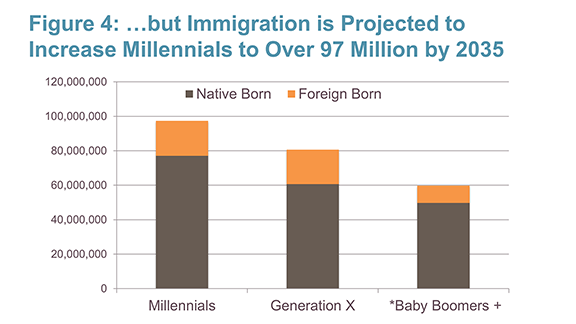

Immigrants also make up a small but growing share of millennials. In 2015, 9.6 percent of millennials were foreign born compared to 21.4 percent of Generation X, and 15.3 percent of baby boomers (Figure 3). However, according to the latest Census Bureau population projections, the share of millennials who are foreign born is expected to rise to 20.9 percent in 2035 when they are age 30-49, which will boost the number of millennials to 97.3 million (Figure 4).

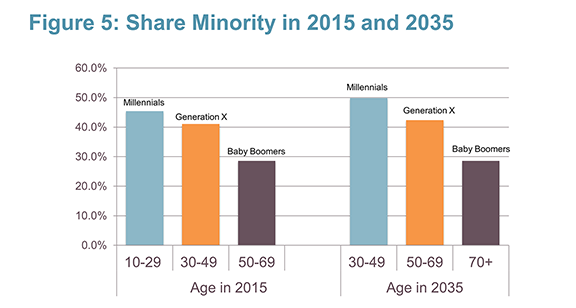

Finally, the constant-age-span approach allows us to identify significant generational differences in race and ethnicity. Overall, in 2015, 45.4 percent of millennials, 41 percent of Generation X, and 28.6 percent of baby boomers were minorities (i.e. non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Asian/Others, or Hispanics of any race). Moreover, because of continued immigration, the share of millennials who are minorities is projected to rise to almost 50 percent in 2035 and the share of Generation X is projected to rise slightly to 42.4 percent. In contrast, the share of baby boomers who are minorities is projected to hold constant at 28.6 percent.

These differences reflect changes for both foreign-born and native-born members of each generation. In 2015, fully 85 percent of both foreign-born millennials and foreign-born members of Generation X were minorities. In contrast, only 78.5 percent of foreign-born baby boomers were minorities. Moreover, while 41.2 percent of native-born millennials were minorities, only 29 percent of native-born members of Generation X and 19.6 percent of native-born baby boomers were minorities (Figure 5).

Looking forward to 2035, the size of the baby boom cohort will drop to about 60 million people because a growing number of baby boomers will pass away. Many millennials and members of Generation X will want to live in the housing units formerly occupied by those baby boomers. Their ability to do so will not only be shaped by the fundamental economic and social changes discussed above but also by whether the large numbers of racial and ethnic minorities in these two generations will have full access to those housing markets, and with it, the ability to achieve the American dream.