COVID-19 and Financially Vulnerable Homeowners: National Trends and Voices from Brockton, Massachusetts

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic slowdown, millions of homeowners across the United States are financially vulnerable. To assess COVID-19’s potential impacts on homeowners, we interviewed homeowners and housing stakeholders in Brockton, Massachusetts and analyzed national data on homeowners who rely on income from at-risk industries.

The effects are already being felt in Brockton, a post-industrial city located 25 miles south of Boston that has seen a resurgent housing market and renewed activity in its struggling downtown over the last decade. Since September 2019, Sharon has used interviews and ethnography to study the financial and practical challenges of first-time homeownership in this city. Within expensive metro Boston, Brockton had become attractive to many homebuyers of color: in 2017, one in five mortgages extended to black households in Massachusetts were in Brockton, even as the city only accounted for 1.7 percent of state-wide loans. As COVID-19 spread across the United States, Massachusetts residents were asked to shelter in place, and as some Brockton homeowners lost their income and jobs, many began to worry about whether they could pay their mortgages in the months ahead.

Cynthia Pendergast, the Program Director at NeighborWorks Housing Solutions in Brockton, said they have been contacted by many concerned residents who are now zero income households. People are asking about rental assistance and are worried about how to make their mortgage payment. Cynthia expects to hear from many more affected residents in the weeks and months to come.

Jeremy, a forty-five-year-old mortgage loan officer, was one such concerned Brockton homeowner. COVID-19 brought back memories of the 2007 housing crisis, when he lost his house and filed for bankruptcy: “I was able to weather through the storm, but I don’t know if I could do it again.” He was anxious about how COVID-19 would affect his commission-based income and called his mortgage company: “What they said was [..] you don’t have to pay your mortgage. It won’t go on your credit report, but you have to pay it within the next 90 days after the grace period.” If he did lose his income, such a forbearance agreement would offer little relief.

National data indicate that many people in other locales face similar challenges. Indeed, the jobs most at-risk to the current economic disruption are prevalent across the country. According to our tabulations of the 2018 American Community Survey, nearly 45.5 million people worked in an at-risk industry within the prior year, including 32.0 million who worked at least 48 weeks. Most of these full-time, at-risk employees worked in retail (12.8 million), entertainment (11.4 million), and various service industries (6.5 million). Retail industries include automobile dealerships, electronics stores, and department stores; entertainment industries include museums, performing arts centers, and restaurants; and service industries include barber shops, salons, and drycleaners. Smaller numbers of at-risk employees also worked in transportation services like air and rail travel (842,000), travel arrangement services (289,000), and oil and gas extraction (118,000).

Collectively, these at-risk full-time workers lived in 24.9 million US households. More than half of these households—59 percent, or 14.7 million in total—were homeowners, including 43 percent (10.6 million) with a mortgage. Overall, nearly one in five American homeowners (19 percent) were reliant on at least one household member employed in an industry now at risk due to COVID-19, including 22 percent of all homeowners with a mortgage.

Many of these households were already more vulnerable to economic shocks. For example, homeowners who exclusively relied on wages earned in at-risk industries had higher housing cost burden rates and lower household incomes on average compared to homeowners in less vulnerable industries.

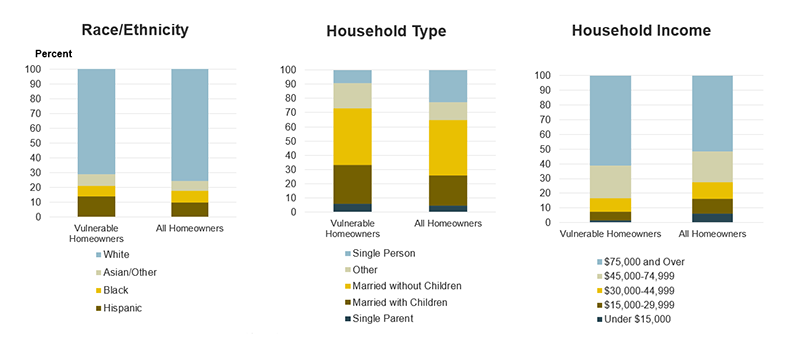

Moreover, homeowners who had at least one household member working in an at-risk industry were more racially and ethnically diverse than all homeowners. Indeed, 29 percent of such homeowner households were headed by a racial or ethnic minority, about 5 percentage points higher than the share of all homeowners. Most of this difference comes from Hispanic households, who comprised 14 percent of vulnerable homeowners but only 10 percent of all homeowners (Figure 1). Fully one-third of vulnerable homeowners (33 percent) had children under 18, compared with only one-quarter (26 percent) of all homeowners. An even higher share of vulnerable homeowners with a mortgage (38 percent) had children in the home.

Figure 1: Vulnerable Homeowners Are More Likely to Be Hispanic, Have Children, and Have High Incomes

Notes: Vulnerable homeowners are those with household members that worked at least 48 weeks in the prior year in an industry at-risk to job losses due to COVID-19. Other household types include all other family and non-family households, including unmarried couples. White, black, and Asian/other households are non-Hispanic. Hispanics may be of any race.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

Homeowners with mortgage payments experience unique challenges in the present crisis. First, homeowners with a mortgage face a heightened risk of foreclosure. Second, these homeowners have much higher monthly housing costs than other households. In vulnerable households, the typical monthly housing costs were $1,570 for homeowners with a mortgage, more than triple the typical cost for homeowners without a mortgage ($520). By comparison, the median rent for renters in at-risk industries was $1,120 per month.

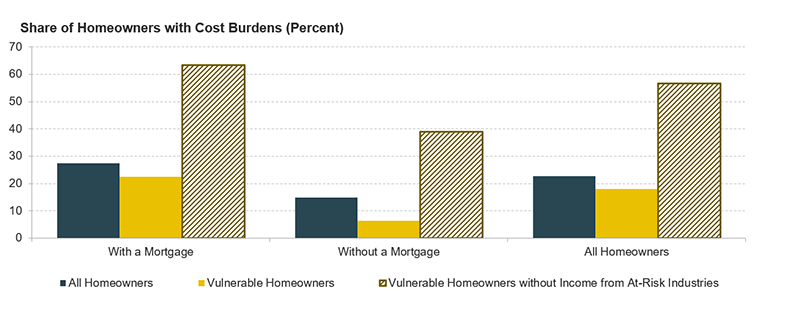

While some homeowners already faced housing affordability challenges under normal conditions, many homeowners in at-risk industries were middle- and upper-income households. Fully 61 percent of vulnerable homeowners had household incomes above $75,000 in 2018. The median household income for those with a mortgage was $97,200 in 2018, nearly twice the income of a typical renter. These households faced modest affordability challenges: only 23 percent of vulnerable homeowners with a mortgage were housing cost burdened, meaning they spent more than 30 percent of their income on housing, compared with 27 percent of all homeowners with a mortgage (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Homeowners, Especially those with Mortgages, Would Face Severe Affordability Challenges without Income from At-Risk Industries

Note: Vulnerable homeowners are those with household members that worked at least 48 weeks in the prior year in an industry at-risk to job losses due to COVID-19. Cost-burdened households pay more than 30% of income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to have burdens.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

By and large these homeowners are reliant on employment that has become at greater risk of termination or a reduction in hours. A substantial decline in wages for an extended period would present major affordability challenges to these homeowners, in addition to the heightened foreclosure risk. If you subtract the wage, salary, and self-employment income of workers in at-risk industries, the median household income for homeowners with a mortgage declines by more than 50 percent, to $45,000 annually. As a result, the cost-burden rate for vulnerable homeowners with a mortgage would skyrocket over 40 percentage points to 63 percent. In other words, without the income from full-time workers in at-risk industries, an additional 5.7 million homeowners would be cost burdened, including 4.3 million homeowners with a mortgage.

Of course, not all these households risk becoming cost burdened or facing foreclosure. Even many workers in at-risk industries will keep their jobs. Some who lose their jobs will be able to find other sources of income. With a quick recovery, most will be able to return to work or regain their hours.

But even the best-case scenarios require significant public intervention to support homeowners through this period of unemployment. Several recently enacted laws provide some relief. The $2 trillion aid bill, for example, includes expanded unemployment benefits as well as provisions to keep small businesses afloat and incentivize them to keep workers on their payrolls. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) also suspended foreclosures for at least sixty days, for borrowers with mortgages backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the FHA. Nonetheless, many mortgages do not fall within these provisions and it remains uncertain whether these policies will protect homeowners in the long run.

Locally, organizations are also developing interventions. NeighborWorks Housing Solutions has extended funding and loosened eligibility requirements for its financial assistance program, Residential Assistance to Families in Transition, to help families avoid eviction, foreclosure, and homelessness. Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance (MAHA), an organization which has supported affordable and sustainable homeownership since 1985, has called for a “mortgage freeze” in Massachusetts. Tom Callahan, MAHA’s Executive Director, contrasted this against typical forbearance agreements—such as the one that Jeremy’s lender had offered him in Brockton—which only delay payments for a few months and then require people to pay within short order. “Those types of programs are not going to work,” Tom said. He instead wanted to see lenders “taking those suspended payments and putting them on the back end of the mortgage.”

While the financial impacts of COVID-19 on homeowners will become clearer over time, the severity of the problem requires an immediate and comprehensive response. “Solutions have to be big and bold,” Tom said, “and probably have to be sustained over a multi-year period, so that we really do recover from this, and help people who were impacted.”