Can Public Housing Play a Role in a New American Social Housing System?

Lately there’s been a lot of excitement in US housing policy circles about the idea of social housing. Inspired by what they have seen in Europe, advocates of social housing envision a system of government or government-funded agencies that develop, own, and manage housing for low-income people outside the private for-profit market. Social housing agencies, the proponents believe, should be energetic, entrepreneurial, mission-driven agencies. Of course, the US already has several low-income housing programs. The oldest and best known of these is public housing, which provides homes to more than 900,000 households.

Might the public housing program be a key component of a new system of affordable housing? In a new paper, “Problems and Progress: Public Housing in an American Social Housing System,” I attempt to answer that question.

In a sense, the current push for social housing is an example of history repeating itself. Almost a century ago, a small band of progressive-era reformers and socialists looked to Europe for models of affordable housing programs, which they referred to as municipal, public, or, yes, social housing. With the support of liberal interest groups—including organized labor and big-city mayors—the “public housers,” as they called themselves, persuaded Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration and Congress to enact a national public housing program.

Under the Housing Act of 1937, locally established public housing authorities (PHAs) could build and manage residences rented to low-income households. The federal government would subsidize the PHAs to construct housing projects by signing contracts to pay “annual contributions.” After they built the projects, the PHAs would use the rent revenues to cover the costs of operations and maintenance.

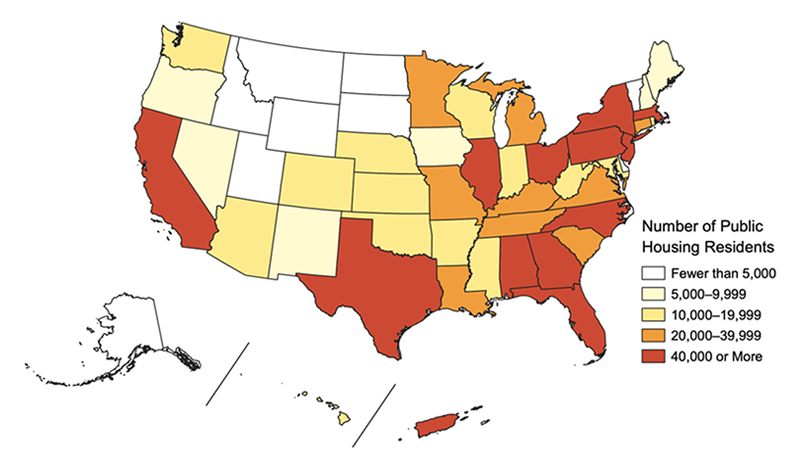

Lacking a groundswell of demand for public housing, the public housers proselytized state and local governments to join the program. They were most successful in places with liberal political cultures or a willingness to partake of federal largesse. As a result, among the states, New York, where the political campaign for public housing originated, has by far the most public housing residents, and Texas, Alabama, and Georgia, former Democratic Party bastions in the deep South, also have large public housing populations (Figure 1). The largest PHAs—which own more than half of all public housing stock—are located in the nation’s major metropolitan areas. Most PHAs, however, operate a small number of dwellings in medium or small jurisdictions.

Figure 1: Public Housing is Unevenly Distributed Across the Country

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2023 Picture of Subsidized Households.

Notes: Includes data for all fifty states and Puerto Rico.

Since it was established, public housing has been beset by challenges. The program endured political attacks from conservatives and private industry, local opposition to projects, and meager appropriations from the federal government. At the same time, for years housing authorities took a paternalistic attitude toward their tenants, whom they routinely segregated by race. Over time, public housing attracted fewer working-class households and increasingly became the housing of last resort for those with the lowest incomes.

Nonetheless, a fundamental and often overlooked problem of the public housing program has been its organizational culture. The financial dependence of PHAs on the federal government encouraged their board members and directors to become bureaucratic and more focused on Washington administrators than their tenants. As early as the 1950s, Catherine Bauer, an author of the 1937 law and a leading public houser, lamented that the local PHAs had lapsed into “excessive caution, administrative rigidity and lack of creative initiative.”

Officials in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations tried to spur the PHAs to action, but to no avail. Thus, starting in the 1960s, liberal policymakers sought alternative ways to produce low-income housing. The most successful of these, the Section 8 program (created in 1974) and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program (enacted in 1986) subsidized private nonprofit and for-profit enterprises rather than government agencies. In addition, the government’s experiment with rent supplements for existing private rental units evolved into the current Housing Choice Voucher program.

As for public housing, by the 1970s, it came to be seen as a social welfare program, catering to very low-income households, including people on government financial assistance. To protect public housing tenants from paying rents beyond their means, Congress capped the rents at 25 percent of tenants’ incomes (later increased to 30 percent) and, to help make up the shortfall, began providing PHAs with supplemental appropriations. At the same time, however, the federal government gave the PHAs additional responsibilities, including administering rental vouchers and providing social services aimed at making their clients financially self-sufficient.

By the 1980s, public housing had reached a critical point. Apartment vacancies, physical deterioration, and crime plagued large projects in big cities. There and elsewhere the backlog of maintenance issues required expenditures far beyond what PHAs could obtain. Moreover, Congress resisted new appropriations for public housing and in 1998 prohibited PHAs from undertaking new construction that would increase their housing above the number of dwelling units they already owned.

In response to these predicaments, since the 1990s the government has adopted administrative and financial reforms that would allow PHAs to break away from traditional public housing procedures. The reforms encouraged PHAs to move previously discrete public housing funds to pay for a range of operations, to develop mixed-income residences with private partners, and to convert public housing contracts to project-based Section 8 subsidies. With these measures PHAs could redevelop their properties with their own subsidiary companies or private partners and create mixed-income communities by combining public housing allocations with low-income housing tax credits and private financing.

In other words, if housing authorities took advantage of the reforms, they could become the entrepreneurial social enterprises that advocates of social housing hope for.

It appears that this transformation has begun. A number of large, high-performing PHAs have exploited new ways to finance, develop, and own low-income residences, and, as a result, control tens of thousands of units outside the traditional HUD-assisted public housing stock. These proficient authorities are well suited to expand their activities, for example, by providing services to other housing agencies or operating across large geographic areas. So far, however, most PHAs, especially those in small towns and rural areas, have not fully exploited the reform programs. Perhaps in time they will. My new paper suggests that these housing authorities will have to surmount their history and present circumstances to become agents of a new social housing order.