A Blueprint for Intergenerational Living

Across the nation, intergenerational residential communities—places that intentionally house and engage people of all ages—address a host of today’s most pressing challenges, including social isolation, housing affordability, and access to supports and services, yet at present they are home to a relatively small number of people. A new report published this week by Generations United, Healthier Lives Across Generations: A Blueprint for Intergenerational Living, offers strategies for addressing barriers to the expansion and scaling of this promising housing alternative.

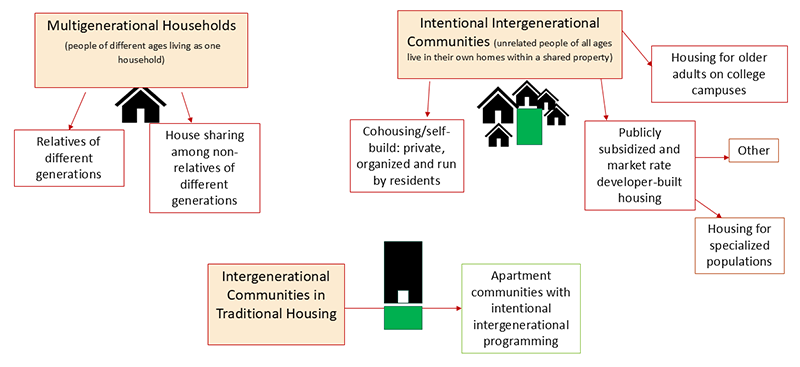

While intergenerational living encompasses a range of residential situations, including multigenerational households (Figure 1), the Blueprint focuses on intentional community settings in which unrelated households live on a shared property but in their own housing units, with a dedicated focus on fostering relationships across ages. Community life is key and mutual support among neighbors common.

Figure 1: Intergenerational Housing Models

These communities include those that are resident-developed and run (e.g., cohousing); apartment buildings that deliberately serve mixed ages and offer social services and community amenities like One Flushing in Queens, NY; and models that serve specialized populations and are supported by programs and staff. Examples of the latter include Bridge Meadows, Hope Meadows, and Treehouse Foundation, all of which are home to families fostering and adopting children, as well as older adults, who all engage in rich community life. Another model is H.O.M.E. in Chicago, which offers several types of intergenerational settings in income-restricted housing. In these communities, site planning, thoughtful design, and programming encourage interaction among generations.

The new Blueprint is co-authored by the Center’s Housing an Aging Society Program and the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston. It builds on findings from a small symposium held at Harvard in the spring of 2024 as well as previous research, including the Center’s examination of intentional intergenerational communities in Germany and their lessons for the US, conducted with the German Marshall Fund. In that work, we identified both general and US-specific challenges to making these options more widely available; these include difficulties identifying, acquiring, and holding sites while funding comes together; navigating the requirements of multiple public subsidies in a way that supports intergenerational housing; securing and nurturing long-term partnerships between housing entities and service providers; sustaining community (and a mix of ages) as residents move in and out; and meeting individual as well as community needs as they change and evolve.

There are several ways to address these challenges, and the Blueprint identifies four pathways:

- Building evidence for the benefits of intergenerational living, and in particular how it affects residents’ health and satisfaction. For older adults, a key metric is whether these settings extend functional ability and capacity to live in the community, and if so, through what mechanisms.

- Expanding awareness of these models among the general public and in policy conversations about affordable housing and economic security for all ages. In addition, market research is needed about intergenerational living; it is a model that will not suit everyone, but given the relatively small number of opportunities today, it is likely that many who might pursue these types of settings are not aware they exist or are possible.

- Advancing policy and financing tools that support intergenerational communities. This might involve the development of new programs that incentivize or help to pay for these settings, that better align programs that subsidize housing with those that subsidize services, or that remove regulatory or programmatic barriers (e.g., zoning barriers, requirements of subsidy programs that can make mixed-age housing difficult).

- Sharing lessons learned from existing communities about financing and design, operations, and sustaining both individuals and the entire community over time, as children grow up and older adults might need increasing levels of support, and as residents come and go over the years.

These strategies, detailed in the Blueprint, can help address one additional challenge: the perception that intentional intergenerational communities are one-off or niche solutions to our significant challenges around housing and social connection—wonderful where they exist, but not scalable. It is true that each community is a unique expression of the people (visionary leaders, residents, and in some cases staff) who have built and sustained it. But that does not mean scale is impossible, particularly if we address challenges common to many types of intergenerational communities.

There are roles for government, advocates, industry, and philanthropy in translating the Blueprint’s recommendations into action and ultimately, in expanding a promising housing alternative that serves all ages.