As Economy Reopens, Guidance Must Consider Older Adults’ Living Situations

Rates of severe illness and mortality from COVID-19 have been highest among older people. As the nation’s stay-at-home orders gradually lift, most strategies for reopening endorse a staged approach and recommend that those most vulnerable to illness continue to shelter in place. Yet many older adults, and others with preexisting conditions, live in households or buildings with people who may increasingly be out in the world, at work, shops, schools and daycares, or social events. Those who live in close contact with others—either in multifamily buildings or multigenerational households—are disproportionately people of color, and indeed, rates of severe illness are higher among older adults who are Black and Hispanic than among those who are white.

Older Adults in Multifamily Buildings

According to analysis of the American Housing Survey, in 2017, 5.7 million households headed by someone age 65 or over lived in multifamily buildings, including 17 percent of households aged 65-79 and 24 percent of those age 80 and over. While the chance of living in a multifamily building increased with age, so too did the likelihood of living in a large building: while 9 percent of those 65-79 lived in buildings with 20 or more units, 18 percent of those 80 and over did so. Fully 11 percent of those 80 and over live in buildings with 50 or more units. Most of these units are occupied by renters though these figures also include those living in condominiums, and the majority of the buildings in which older people live are “all-age” (e.g. not restricted to older adults).

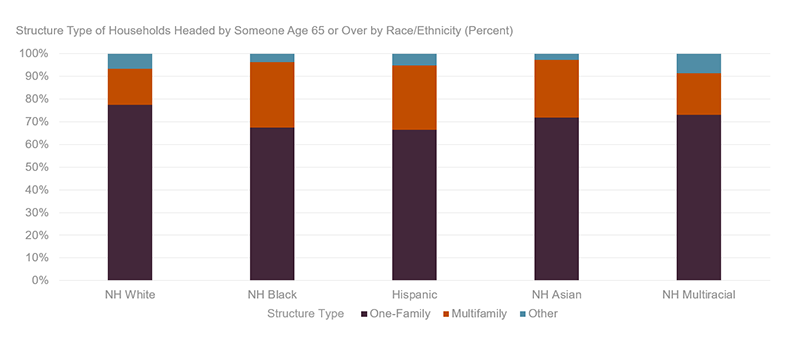

The likelihood of living in a multifamily setting varies by race/ethnicity. As of 2017, 29 percent of households headed by non-Hispanic Black older adults lived in multifamily housing, as did 26 percent of Hispanic and 25 percent of non-Hispanic Asian older households. In comparison, 18 percent of non-Hispanic multiracial and 16 percent of non-Hispanic white households resided in multifamily housing (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Black, Hispanic, and Asian Older Households Are More Likely to Live in Multifamily Buildings

Note: NH refers to non-Hispanic.

Source: Joint Center of analysis of American Housing Survey 2017.

There can be many benefits to living in apartments or condos, such as reduced maintenance and, for some, the availability of amenities and services in the building or in denser neighborhoods. During the pandemic, building staff or neighbors may help older residents procure groceries or other necessities. Yet it is also true that most of these buildings include common spaces where it can be more difficult to socially distance – common hallways, lobbies and mailbox areas, laundry facilities, waste disposal spaces, and elevators, for example. None of these are easily avoidable (and while there may be stairs in elevator buildings, avoiding the elevator is not possible for those with difficulty navigating steps, as well as in high-rises.) While there is limited data on infection rates by building type, there is a great deal of concern about contagion in indoor common areas, and numerous articles have been written over the past several months on the safety of elevators alone. Of older people living in multifamily buildings, fully 27 percent of those aged 65-79 and 45 percent of those age 80 and over lived in buildings with elevators—totaling 1.6 million households—as of last count in 2013.

The CDC offers guidance for operators of apartment buildings and other shared housing, including recommendations for disinfecting common spaces, policies requiring masks or limiting staff visits to private apartments, and programming the use of certain facilities (such as instituting one-way flow through halls or stairs, or limiting the number of people using an elevator at the same time). As some residents return to work or school—particularly in non-age-restricted housing—more people will be presumably moving through these spaces, making it even more important to take these steps to protect neighbors who are older or otherwise more vulnerable to illness.

Continuing to check on and support older residents—or building better systems to do so—will remain critical too, as needs for assistance and social contact will not abate for those continuing to shelter at home. In fact, supports may become even more essential: first, neighbors and family providing informal aid may return to work and have less time to help, and second, as more of the public are allowed to use shops, parks, and the like, public spaces may become even more fraught for those vulnerable to serious illness.

Older Adults in Multigenerational Households

As we highlighted in our most recent Housing America’s Older Adults report, one in five older people lives in a multigenerational household, which in our definition means homes with a person age 65 and over living with at least one other adult relative of another generation. In 2018, 9.3 million people age 65 or over lived with their grown children or grandchildren and 442,000 lived with their parents or in-laws, while another 84,000 lived with both. People are more likely to live multigenerationally at older ages: 19 percent of those aged 65-79 do so, while 24 percent of those 80 and over live with family of other generations.

Multigenerational living is more common among Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, and non-Hispanic Black households than among white older adults for reasons relating broadly to both economic disparities and culture. As of 2018, just under 40 percent of Hispanic adults aged 65–79 and 47 percent of those age 80 and over lived with other generations, with similar shares among older adults who are Asian or other non-white race/ethnicity. Among older adults who are Black, 27 percent of those aged 65-69 lived multigenerationally as did 36 percent of those age 80 and over. By comparison, 14 percent of white older adults aged 65-79 lived in multigenerational households, as did 18 percent of those age 80 and over. As previous analysis by my colleague Whitney Airgood-Obrycki has shown, non-white multigenerational households are more likely to live in overcrowded conditions and to include people working in jobs requiring them to be close to other people, increasing risks of catching COVID-19.

As with apartment living, there are many potential benefits to living multigenerationally, including lower housing costs and easier access to informal care (including care for older people but also young children). During stay-at-home advisories and orders, older people in multigenerational households may be less isolated than those living alone. They may also have more immediate access to help obtaining necessities like food and medication. Yet householders returning to higher-contact activity increases risks of transmission within the home. The CDC’s guidance for those living in “close quarters” recognizes that if “your household includes one or more vulnerable individuals then all family members should act as if they, themselves, are at higher risk,” and advises that no one leave the house unless “absolutely necessary.” This advice could get more difficult over the summer and early fall as states reopen and younger adult workers need to return to work and children to daycare, camps, and school. Within the household, the CDC advises frequent disinfection, not sharing personal items, and setting up space within the home for vulnerable members to self-isolate from other household members if necessary—though this too can be difficult in crowded homes. Some advice suggests that family members returning from public places wash up before leaving work, change clothes, and remove shoes upon return.

The fact that many in living situations with close proximity to others are older adults of color has much to do with the ways that structural racism has shaped access to housing and neighborhoods and, not coincidentally, these same forces have contributed to higher rates of serious illness among Black and Hispanic people of all ages. Many do choose apartment living because it offers conveniences and amenities, and multigenerational arrangements are often a personal choice influenced by culture and the needs of different members of a household, as well as finances. The fact remains, however, that those who have means may have larger spaces and access to paid assistance, which doesn’t solve all problems of social distancing at home (such as loneliness) but can alleviate some of the contagion risks; for this group, close proximity may not be quite “as close.”

Guidance that older people and others at higher risk of serious illness continue to isolate at home is offered in the spirit of protecting older people’s health. Yet adhering to this advice does not eliminate risks, especially for those in close proximity to others. With about one-quarter of households headed by someone 80 over living in multifamily buildings, and a fifth of individuals of the same age living in multigenerational settings, responsibilities for keeping people safe cannot rest with individuals alone. While much guidance from the CDC is aimed at building operators and family members, municipalities have a role to play as well in ensuring that older people in dense environments have access to needed goods and services; the Center for an Urban Future lays out a host of suggestions relevant to local government and nonprofits.