The 2018 GSE Stress Test Results: A Major Policy Success and Its Implications for the Proposed Capital Rule

New stress test results for the two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, released on August 15, did not seem to get much media coverage beyond some specialty press. They should have, for the results confirmed a major policy success in the extreme de-risking of the two companies while in conservatorship: stress results are down about 80 percent in the five years since they were first measured! This, in turn, has important implications for the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s much-awaited capital rule that would apply to the GSEs post-conservatorship.

These stress tests, done each year since 2013 under a government-designed regimen known as DFAST (Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test), are similar to the well-publicized stress tests administered to large banks via the Federal Reserve. The regulator and conservator of the GSEs, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), closely organizes, supervises, and monitors the testing process and receives the results. It all starts with the same economic and financial “severely adverse scenario” specified by the Federal Reserve. The latest results were based upon the GSE’s year-end 2018 financial statements.

Because the GSEs are in conservatorship, and are not allowed to accumulate capital beyond a small buffer, the results of the stress test are expressed in terms of how much loss they would incur, which would then (after that small capital buffer is consumed) generate a draw upon the US Treasury to prevent the net worth of the two companies from going below zero (which is required in the legal agreement by which the Treasury supports the two companies). Banks have their results expressed more in terms of capital adequacy ratios, but otherwise it’s the same test, administered in the same manner, to show risk in the same way.

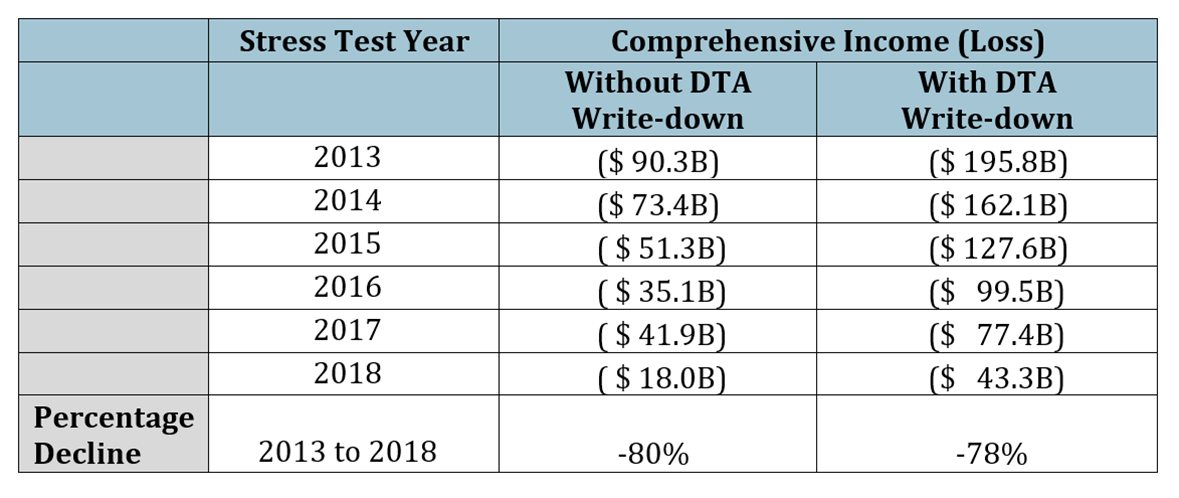

The results have been a very impressive – and quantitative – measure of how much less risk the GSEs have on their books now than they did in the early years of conservatorship. For both Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, immediately below are the combined results over the six years, all as reported annually by the FHFA. (The results are reported in two ways, both with and without the establishment of a “valuation allowance on deferred tax assets.” This somewhat complicated accounting issue relates to the fact that the results published according to SEC requirements (which are under GAAP – Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) are different from those used for paying income taxes. Without going into the intricacies of it all, if the prospect for future earnings in a stress scenario are poor enough, then there must be an up-front accounting loss taken to write down the “deferred tax asset” (DTA) on the GAAP balance sheet, increasing even more the earnings loss in that stress scenario.)

Table 1

In short, the modeled loss by the two companies in the severely adverse scenario – which is comparable to, and in some ways arguably worse than, the 2008 financial crisis – has strongly trended down over the five years since the stress tests were first initiated for the GSEs, resulting in the approximate 80 percent decline. (The particulars of the Federal Reserve-specified stress change somewhat from year to year, but have nevertheless remained reasonably consistent over the six years shown, seemingly using the 2008 financial crisis as its core. The exception were some unusual features in 2017, mostly reversed in 2018.)

This giant risk reduction reflects several causes:

- First, the risk of a mortgage is strongly tied to the ratio of each home’s outstanding loan amount to its current market value (its loan-to-value, or LTV, ratio), and home prices have risen strongly since they bottomed in 2011.

- Second, the GSEs made a major effort to reduce their “legacy” mortgage assets, consisting mostly of defaulted loans that have been bought back from mortgage-backed security (MBS) investors to exercise the credit guarantee given to them by the GSEs, as well as the (almost always impaired) non-agency mortgage securities purchased prior to conservatorship.

- And third, the GSEs implemented credit risk transfer (CRT) in large scale on new single-family guarantees, so that a growing portion of the stress modeled losses are for the account of the CRT investors rather than the GSEs. (This was also true to a degree for multifamily lending.)

There are two important and strategic implications of these results.

First, with all the politicized commentary about the GSEs, it is hard to know what to believe: Are they just a few economic bumps away from collapse and dragging down the US economy? Or are they very much reformed, being responsibly managed in conservatorship to do their essential function of mortgage loan financing while becoming much less a source of potential systemic risk? The results strongly support the “reformed in conservatorship” viewpoint. They also have a high degree of credibility, as they are based upon the Federal Reserve-provided severely adverse scenario used for large banks, rather than something arguably politically biased to “help homeownership” by understating risk.

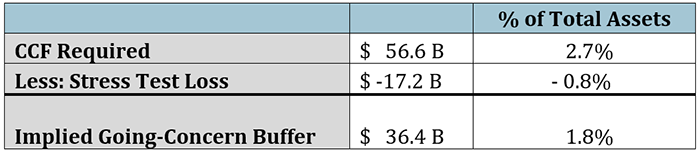

Second, they give some insight into the amount of capital the two companies need, which is especially relevant now as the FHFA finalizes its proposed post-conservatorship capital rule to apply to the two companies. Take the case of Freddie Mac: its 2018 DFAST severely adverse loss was $8.4B (without a DTA write-down) and $17.2B (with such a write-down). To be conservative, let’s use the larger number – even though it is highly arguable no such write-down would be needed in the most recent stress results (because the company returns to profitability soon enough to very likely not trigger the accounting requirements needed to write-down the DTA). According to the stress test approach used by the banks, capital should be enough to (1) absorb the severely adverse scenario losses, plus (2) have a remaining residual amount of capital adequate to maintain market confidence after the stress event (known as the “going-concern buffer,” the size of which is very much a judgment call by the regulators). We also know that Freddie Mac reported in its 2018 yearend financial results press release that the amount of capital required by the Conservatorship Capital Framework (CCF) – which has the same capital formulae as the risk-based portion of the proposed capital rule and is currently used by the two GSEs for risk-reward decision-making while they are in conservatorship – was $56.6 billion for the fourth quarter of 2018, when Freddie Mac’s total assets were $2.1 trillion.

So, we can do the obvious calculations:

Table 2

Do we then consider the residual $36.4 billion “implied going-concern buffer” enough to maintain market confidence? Given that it is more than double the severely adverse scenario stress test loss, there is a good argument it does. But as the FHFA has never formally and publicly made the judgment call of how to calculate a total going-concern buffer for the GSEs, we can only posit that it is indeed adequate.

Regardless of the specifics of what the FHFA comes out with in its capital rule, there is no denying that the stress test results are a credible reminder how de-risked the GSEs are today versus just five years ago. The stress loss, at just 0.8 percent of assets, is a small amount (and would only be 0.4 percent if no DTA write-down is assumed), especially when compared to the 3 to 5 percent loss ratio range that I have heard policymakers most commonly discuss as being generated during the financial crisis.

It’s a quiet but major policy success that should get more attention in Washington.