Pandemic Highlights Disparities in High-Speed Internet Service

One year before the pandemic began, almost one-fifth of households in the United States did not have high-speed internet service. This digital divide put many households in a difficult situation when the pandemic forced much of life—from school to work to medical appointments—to go online. According to Census data, those least likely to have high-speed internet in 2019 were households of color, rural households, and low-income households. For some without high-speed internet, the service is available but not affordable, but for others it is simply not available. Several federal programs have been implemented to address both issues of cost and access.

At the start of this summer, many households began receiving money from the $3.2 billion Emergency Broadband Benefit program that was included in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. The program provides $50 per month towards internet services for eligible households (which includes both low-income households and those who lost employment income since the start of the pandemic) and will last until funding runs out. The American Rescue Plan also included $7 billion for schools and libraries to expand and improve internet access. This funding could be augmented substantially by the bipartisan infrastructure bill currently being considered by Congress, which proposes $65 billion to expand broadband access.

The Emergency Broadband Benefit program could ease the financial strain for many low-income households—who were the most financially impacted by the pandemic—but it cannot help those without access to high-speed service. According to the FCC’s 2021 Broadband Deployment Report (which uses an individual-level measure instead of a household-level measure) 14.5 million Americans lived in areas without access to high-speed internet in 2019, down from 18.1 million in 2018. However, the FCC’s methodology relies on self-reporting by internet service providers, and this approach has been criticized as inaccurate by researchers at BroadbandNow, who estimate that 42 million Americans live in areas without access to high-speed internet.

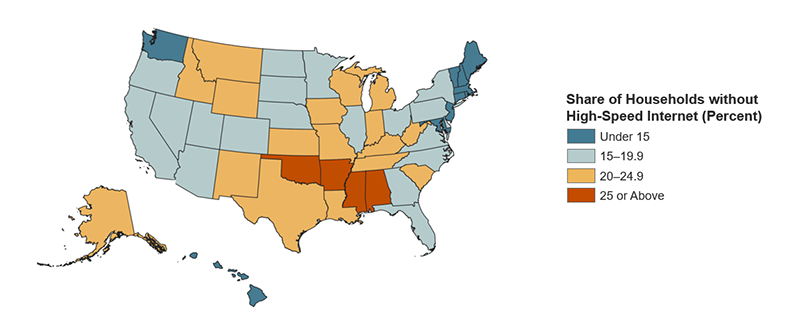

Census data reveal whether households have high-speed internet, but not whether households without high-speed internet are facing barriers of cost or access. Still, the trends of high-speed internet usage provide many insights into where this utility is most needed. Nationally, almost one-fifth of households (19 million) had no high-speed internet service in 2019, according to American Community Survey (ACS) data. This varies greatly by state, from approximately one-third of households lacking high-speed internet in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Oklahoma, to around one-tenth of households in Massachusetts, DC, and New Hampshire. States with large rural areas are more likely to have a bigger digital divide (Figure 1). In all rural areas combined, nearly 29 percent of households (4 million) lacked high-speed internet in 2019, compared to 17 percent of households (15 million) in metropolitan areas.

Figure 1. States with Large Rural Areas Have Larger Digital Divides

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

High-speed internet is increasingly important given the growing need for video conferencing and when multiple people in a household need to use the internet simultaneously. For households with school-age kids, internet needs were keenly felt during the most recent school year, with challenges ranging from insufficient speed to device availability. According to ACS data, households with school-age kids were more likely than households without school-age kids to have high-speed internet. Nearly 16 percent of households with school-age children (aged 6-17) lacked high-speed internet in 2019, compared to 19 percent of households without school-age children.

However, there were many disparities among households with school-age children. Among these households in 2019, 29 percent of those earning less than $30,000 lacked high-speed internet, compared to 23 percent of those earning $30,000-44,999, 18 percent of those earning $45,000-$74,999, and 10 percent of those earning $75,000 or more. Having access does not necessarily remove all obstacles, however. While nearly a third of low-income households lacked high-speed internet service, a Pew Research Center survey conducted in April 2020 found that nearly two-thirds of lower-income parents reported that their children would face digital obstacles with schoolwork during the pandemic.

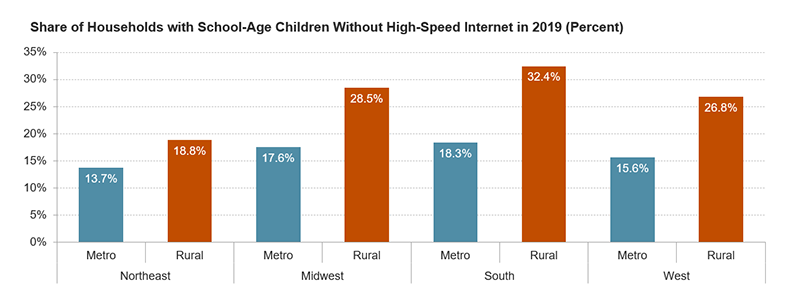

Geographically, rural households with school-age kids were least likely to have high-speed internet, especially in the South, where 29 percent of households lacked high-speed internet, compared to 25 percent in the West, 24 percent in the Midwest, and 15 percent in the Northeast (Figure 2). Households of color with school-age children were generally less likely to have high-speed internet as well. One-fifth of both Black and Hispanic households with school-age kids did not have high-speed internet in 2019, compared to 14 percent of white households, and 9 percent of Asian households.

Figure 2. Rural Households with School-Age Children Are Less Likely to Have High-Speed Internet

Note: Metropolitan areas are defined by the Census Bureau as having at least one urbanized area with a population of 50,000 or more. Rural areas are defined here to mean micropolitan or non-metropolitan. Micropolitan areas have at least one urban cluster of 10,000 to 50,000 people. Non-metropolitan areas fall outside of both types of statistical areas. School-age is defined as 6-17.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

These statistics illustrate the disparities as they existed before the pandemic. As many households lost employment income after the pandemic began, they may have been less able to afford high-speed internet even as it became more important for remote work and school. Another Pew survey found that one-third of low-income households reported difficulty paying for home internet service during the pandemic. The $3.2 billion Emergency Broadband Benefit program was one federal response to that, but a much larger investment is waiting in the wings through the bipartisan infrastructure bill currently being considered by the House. The bill’s $65 billion for broadband internet includes $42 billion for service improvements and $14 billion to turn the Emergency Broadband Benefit into a permanent program. These policies have the potential to improve both cost and coverage for this increasingly important utility after the pandemic made it apparent that homes need to be not only safe and healthy but also well-connected.