Inclusionary and Incentive Zoning in the Six New England States

Almost 200 localities in all six New England states—Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont—use inclusionary zoning programs to help spur the construction of affordable housing. Research I did for this summer identified important similarities and variations in how these programs are structured. My research was part of a project examining the nature and extent of housing affordability issues in the six states, particularly for low-income households and households of color. The research, which was funded by the Federal Home Loan Bank of Boston (FHLBB), will help the bank and members of its Advisory Council develop the bank’s annual Targeted Community Lending Plan and its Affordable Housing Program Implementation Plan.

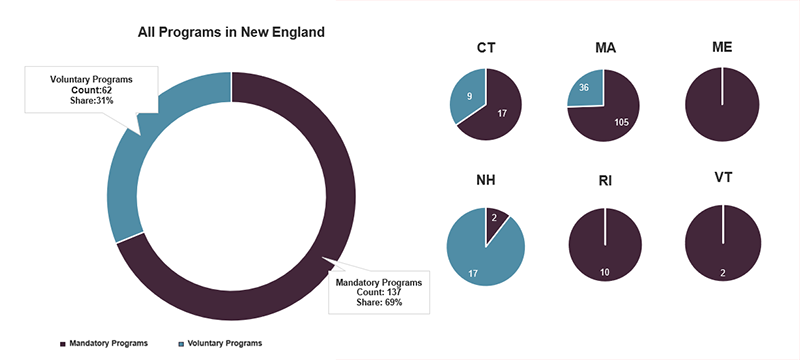

In New England, housing affordability challenges are pervasive due in no small part to an insufficient supply of housing, particularly at the low end of the market. As a result, in 2019, 46 percent of renter households in the region were cost burdened, paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing. One mechanism to address these affordability challenges, adopted by localities in all six New England states as of 2019, was inclusionary or incentive zoning. Almost three-quarters of these programs were in Massachusetts, which has a particularly strong state law (Chapter 40B) that can compel localities to accept developments that include affordable units. Another 18 percent were in Connecticut and Rhode Island, which have similar but weaker state laws. The remaining programs were in the three states that do not have similar laws: New Hampshire (9 percent), Maine (1 percent), and Vermont (0.5 percent).

Differences & Similarities in the Programs

While these programs have the same or similar objectives, they differ in important ways. The bulk of the programs in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island (as well as the two programs in Vermont and the one program in Maine) are mandatory inclusionary programs, which require multifamily developers to set aside a fixed share of units as affordable housing. In contrast, 17 of the 19 programs in New Hampshire are incentive zoning programs that provide some sort of density bonus for developers who voluntarily include a required share of affordable units. In addition, about a third of the programs in Connecticut and a quarter of the programs in Massachusetts are incentive zoning programs (Figure 1).

In most jurisdictions, smaller developments aren’t required or don’t qualify for inclusionary housing incentives. Indeed, affordability requirements or incentives are triggered for projects with under 5 units in just 13 percent of jurisdictions while the majority—just over 50 percent—trigger requirements for projects with between 5 and 9 units. Inclusionary housing requirements kick in for another one-third (34 percent) of jurisdictions for projects that are 10 or more units. The remaining handful use acreage as a key metric rather than project size.

The share of units that must remain affordable also varies. Fully 42 percent of programs in the six New England states require 10-14 percent of units to be affordable; one fifth require 15-19 percent of units to be affordable; another quarter require 20-24 percent; and 9 percent require 25-49 percent of units to be allocated to affordable housing.

Regardless of whether they are for-rent or for-sale, almost 90 percent of programs reserve affordable units for households making no more than 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI). However, 14 New Hampshire municipalities require that rental units be affordable for those making 60 percent of AMI. For owner-occupied units, 14 jurisdictions in New Hampshire set the threshold at 100 percent of AMI, one sets it at 120 percent, and another puts it at 150 percent. In addition, four communities in Rhode Island also set the affordability threshold at 120 percent of AMI for owner-occupied units.

Figure 1: Fully Two-Thirds of Inclusionary Housing Programs in New England Are Mandatory, with New Hampshire Being the Most Notable Exception

Note: Data show the number and share of jurisdictions with inclusionary or incentive zoning programs in New England and by state.

Source: JCHS tabulations of the Grounded Solutions Network’s inclusionary housing database

Are the Programs Effective?

Local policymakers must make a range of decisions about how inclusionary housing programs are ultimately implemented. Program effectiveness not only depends on these details but on other factors such as local and regional market conditions, community preferences, the broader economic context, state-level laws that guide local land-use policymaking, and, of course, the local, regional, and statewide political climates in which key policy decisions are discussed, shaped, and made.

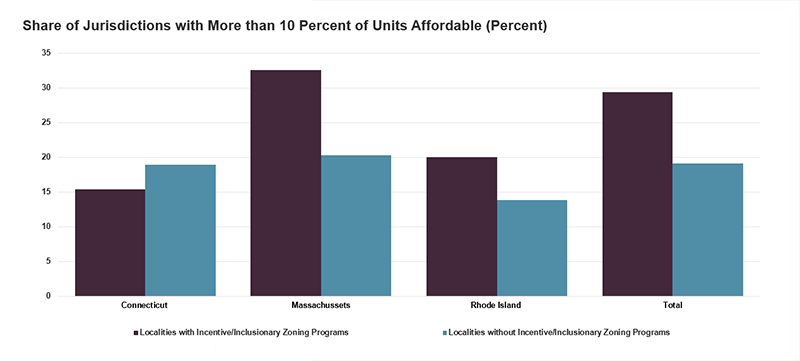

But assessing how many units are produced because of inclusionary housing practices remains difficult because there are no statewide databases, and many localities either don’t have the data or don’t make it easily available. However, my research suggests that in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island 29 percent of the cities and towns that met their 10 percent affordable housing goals had adopted some form of inclusionary or incentive zoning, compared to only 19 percent of localities that had not met these goals. Nonetheless, these results varied by state. In Massachusetts, 33 percent of localities that met the 10 percent threshold had inclusionary housing programs compared to only 20 percent of the localities that have not met that threshold. The pattern was similar in Rhode Island, where the comparable figures were 20 and 14 percent. However, this pattern was reversed in Connecticut where 15 percent of localities that met the state’s affordability goal had adopted inclusionary or incentive zoning compared with 19 percent of localities that had not met the 10 percent goal (Figure 2).

While inclusionary and incentive zoning are among the most common local tools used to spur the production of affordable housing, a handful of localities also have adopted other tools, such as linkage programs, creating affordable housing trust funds, and encouraging the development of Accessory Dwelling Units. While none of these tools on its own can address local or regional housing needs, each can play a useful role in helping make housing more affordable for all of the region’s residents.

Figure 2: Municipalities in Massachusetts and Rhode Island (But Not Connecticut) That Met State Housing Goals Were More Likely to Have Inclusionary or Incentive Zoning

Note: Data show the number and share of jurisdictions with inclusionary or incentive zoning programs.

Source: JCHS tabulations of Grounded Solutions Network’s inclusionary housing database and data from Zillow and state housing and community development departments.