Are Integrated Neighborhoods Becoming More Common in the United States?

The share of the population living in racially and ethnically integrated neighborhoods in the US has increased since 2000, according to our new Joint Center research brief. However, most Americans continue to live in non-integrated neighborhoods, and evidence suggests that some of the recent increases in integration may be the temporary byproduct of gentrification and displacement.

The new brief, “Patterns and Trends of Residential Integration in the United States Since 2000,” assesses whether the nation’s increasingly diverse population is fostering the growth of integrated neighborhoods or whether the choices people make about where to live are reinforcing existing lines of segregation and exclusion. Specifically, we use data from the 2000 Census and the 2011-15 American Community Survey (the most recent data available at the census tract level) to describe the number, stability, and characteristics of integrated neighborhoods.

Because there is no single measure for identifying integrated neighborhoods, our analyses applies two commonly-used definitions to define integration. The first approach—which we refer to as “no-majority neighborhoods”—defines integrated neighborhoods as those where no racial or ethnic group accounts for 50 percent or more of the population. While this definition identifies neighborhoods with a plurality of races and ethnicities, it may exclude some neighborhoods with relatively high levels of integration relative to the median neighborhood in the United States. For example, under this definition, a census tract that is 49 percent black and 51 percent white would be classified as non-integrated.

The second definition—which we refer to as “shared neighborhoods”—uses a broader definition of integration, identifying neighborhoods as integrated if any community of color accounts for at least 20 percent of the tract population AND if the tract is at least 20 percent white. While this definition might be expanded to include neighborhoods in which any two groups account for at least 20 percent of the tract’s population, this definition requires that the neighborhood population be at least 20 percent white because of whites’ long history of exclusionary practices as well as attitudinal surveys suggesting that, on average, whites are less willing that other groups to live in integrated neighborhoods.

Both definitions suggest that the number of integrated neighborhoods—and the share of the US population living in integrated neighborhoods—increased between 2000 and 2011-15 (a time when the white, non-Hispanic share of the population fell from 69.1 percent to 62.3 percent). The number of “no-majority neighborhoods” increased from 5,423 census tract in 2000 to 8,378 in 2011-15, and the share of the US population residing in such tracts increased from 8.0 percent in 2000 to 12.6 percent in 2011-15 (Figure 1).

Similarly, the number of “shared neighborhoods” increased from 16,862 tracts in 2000 to 21,104 tracts in 2011-15, and the share of the US population residing in “shared” tracts increased from 23.9 percent in 2000 to 30.3 percent in 2011-15. These figures are higher than the estimates for “no-majority” tracts, reflecting the broader definition of integration used to define “shared neighborhoods.” Nonetheless, both definitions show increases in integration between the 2000 Census and the 2011-15 ACS.

Notes: “No-majority neighborhoods” are census tracts in which no racial or ethnic group accounts for 50 percent or more of the population. “Share d neighborhoods” are census tracts in which whites account for 20 percent or more of the population and any community of color accounts for 20 percent or more of the population. N=71,806 Census tracts.

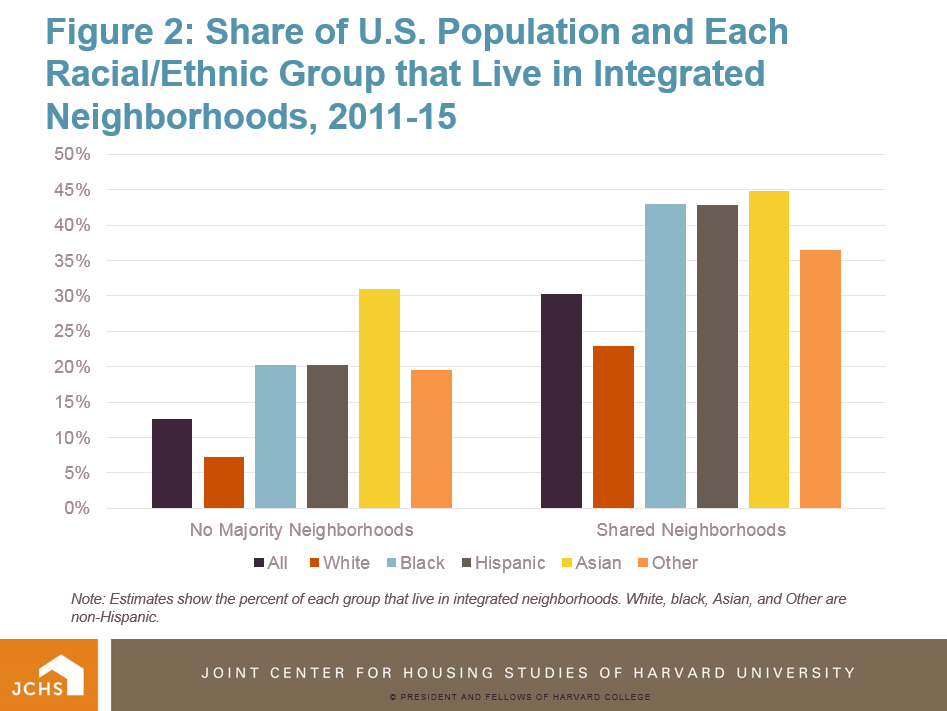

While the share of the population living in integrated neighborhoods has increased since 2000, most Americans continue to live in non-integrated areas, with white individuals the least likely to live in integrated areas. While 12.6 percent of the total US population lives in one of the 8,378 “no-majority” tracts, these neighborhoods include just 7.2 percent of the nation’s whites, compared to 20.3 percent of blacks, 20.3 percent of Hispanics, 30.9 percent of Asians, and 19.5 percent of individuals of other races and ethnicities (Figure 2).

A similar pattern is present within “shared neighborhoods.” While 30.3 percent of the total US population lives in one of the 21,104 “shared neighborhoods,” these neighborhoods include just 22.9 percent of the nation’s whites, compared to 43.0 percent of blacks, 42.8 percent of Hispanics, 44.8 percent of Asians, and 36.5 percent of individuals of other races and ethnicities.

Note: Estimates show the percent of each group that live in integrated neighborhoods. White, black, Asian, and Other are non-Hispanic.

The research brief provides more specific details about the relative composition of integrated and non-integrated neighborhoods by race, ethnicity, and other demographic characteristics. Additionally, it describes the stability of integrated neighborhoods between 2000 and 2011-15, as well as the geographic distribution of integrated neighborhoods across central cities, suburbs, and non-metropolitan areas.

Taken together, this evidence offers support for the conclusion that the number of integrated neighborhoods has increased in recent years. However, it also highlights that this conclusion is subject to two important caveats. First, some portion of the increase in integration reflects neighborhood change processes associated with the gentrification and displacement pressures affecting the central areas of many cities. While some of these neighborhoods may become stably integrated areas, it is not yet clear how many of the newly integrated neighborhoods will become stably integrated and how many will eventually become non-integrated areas.

Second, integrated neighborhoods remain the exception rather than the rule in the United States. The 2011-15 ACS shows that fewer than one in three Americans lives in a shared neighborhood, with just 12.6 percent living in “no-majority neighborhoods.” As the country moves toward a population in which people of color are projected to be a majority by the middle of the century, further growth will be necessary for such changes to produce a more inclusive society.