Affordability Gaps Widened for Renters in the First Year of the Pandemic

In 2020 with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large and growing share of renters were cost-burdened, according to a Center analysis of new experimental data from the American Community Survey (ACS). From 2019 to 2020, the share of renter households with cost burdens rose nearly 3 percentage points. Among renters, the pandemic widened socioeconomic and racial inequalities in housing cost burdens.

In a previous blog, we noted that the 2020 ACS suffered from data collection issues due to the pandemic, which resulted in nonresponse bias the Census Bureau couldn’t fully account for with their typical weighting methodology. The Census released experimental data for 2020 with new weights, though these data are essentially incomparable to previous years. To enable researchers to examine changing trends in the first year of the pandemic, the Census recently provided experimental weights for the 2019 data using a comparable weighting method. In this blog, we use the experimental data to examine how cost burdens changed for renters in the first year of the pandemic.

Cost-burdened renters spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on rent and utilities each month. In 2020, the share of burdened renters reached 46 percent, up a full 2.6 percentage points from the year before. Pandemic job losses that hit renters especially hard widened the affordability gap between owners and renters. Owner cost burden rates rose just 1.0 percentage point in 2020, increasing the gap in cost burdens between owners and renters to nearly 25 percentage points.

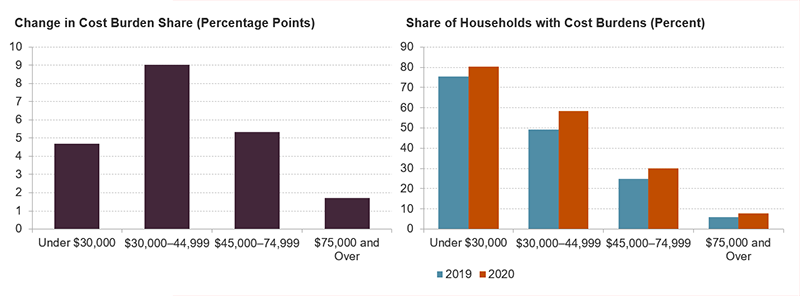

Before the pandemic, cost burdens were highest for lower-income renter households and rising fastest among middle-income renters. This trend continued in the first year of the pandemic. Cost burdens increased by nearly 5 percentage points, to 80 percent, for households making less than $30,000 (Figure 1). Renters making $30,000–45,000 saw their cost burden rate jump by an astounding 9 percentage points to 58 percent, while those making $45,000–75,000 posted rates of 30 percent, a 5-percentage-point rise from 2019. Higher-income households maintained a relatively low burden rate of 8 percent, less than 2 percentage points above 2019 levels.

Figure 1: Middle-Income Renters’ Cost Burdens Soared in 2020

Notes: Moderately (severely) cost-burdened households pay more than 30% up to 50% (more than 50%) of household income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to be severely burdened, while households paying no cash rent are assumed to be unburdened. Household incomes are inflated to 2020 dollars using CPI-U All Items.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2019 & 2020 Experimental American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

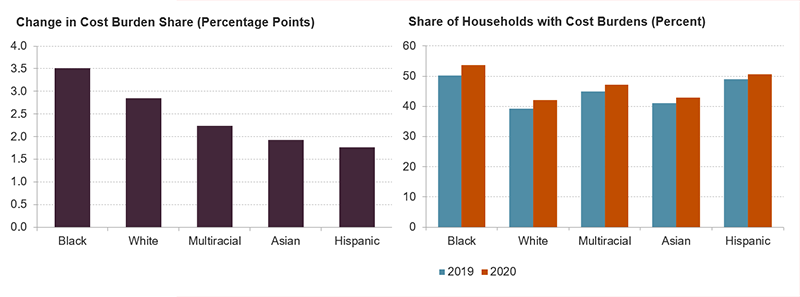

Cost burdens rose fastest among renter households headed by a Black person, widening the existing Black-white affordability gap (Figure 2). Cost burden rates increased 3.5 percentage points for Black renter households, reaching 51 percent in 2020. White households also saw their cost burden share increase rapidly by nearly 3 percentage points, but these renters continued to have the lowest burden rates at 42 percent. Meanwhile, Asian-, Hispanic-, and multiracial-headed renter households fared only slightly better with about a 2-percentage point increase in their burden rates.

Figure 2: The Black-White Affordability Gap Widened for Renters

Notes: Moderately (severely) cost-burdened households pay more than 30% up to 50% (more than 50%) of household income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to be severely burdened, while households paying no cash rent are assumed to be unburdened. White, Black, Asian, and multiracial householders are non-Hispanic. Hispanic householders may be of any race. Householders of another single race are not shown. Native American & Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and another single race categories all had decreasing burdens over this period.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2019 & 2020 Experimental American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

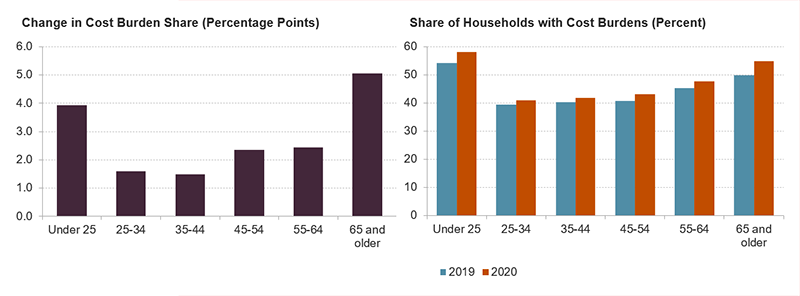

Across age categories, cost burden rates increased most rapidly for renter households headed by someone age 65 or older with a rise of 5 percentage points (Figure 3). Older adult household incomes rose slower compared to other age groups. This may be due, in part, to the high share of older adult households that rely heavily on social security income. In 2020, the cost-of-living increase for social security was just 1.3 percent while median rents for older adults rose much faster. These rent increases put the older adult cost burden rate at 55 percent in 2020. Only the youngest renter households headed by someone under age 25 had higher cost burden shares (58 percent), following a 4-percentage point increase in 2020.

Figure 3: Older Adult Renters Had the Fastest Cost Burden Increases

Notes: Moderately (severely) cost-burdened households pay more than 30% up to 50% (more than 50%) of household income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to be severely burdened, while households paying no cash rent are assumed to be unburdened.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2019 & 2020 Experimental American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

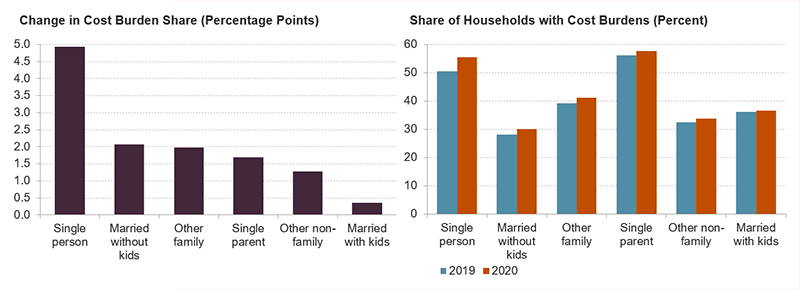

Single-person renter households experienced the largest jump in cost burdens of all household types at 5 percentage points (Figure 4), likely related to the fact that older adults make up nearly a third of these households. It’s also possible that having only one earner meant that single-person households were less able to cope with rising rents and employment income losses in the first year of the pandemic. Interestingly, single parent renters, who have the highest burden rate at 58 percent and who may have been most likely to lose employment income due to childcare disruptions, saw their burden rates rise by just under 2 percentage points.

Figure 4: Cost Burdens Rose Quickly for Single-Person Renter Households

Notes: Moderately (severely) cost-burdened households pay more than 30% up to 50% (more than 50%) of household income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to be severely burdened, while households paying no cash rent are assumed to be unburdened.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2019 & 2020 Experimental American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

The experimental ACS data show that widening affordability gaps by income, race, and household type in the first year of the pandemic compounded existing inequities. Income supplements through expanded unemployment insurance and stimulus checks likely helped offset worsening cost burdens for some. But the overall rise in already high renter cost burden rates is troubling, particularly among the lowest-income and Black renter households. Further income supports and rental assistance will be needed to help renters cope with increasingly unaffordable housing, especially given the record-high rent growth and tight market conditions over the last year that we recently documented in the State of the Nation’s Housing 2022.